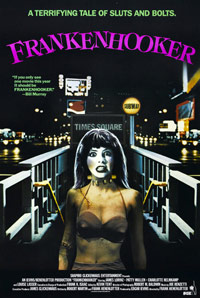

Frankenhooker

Growing up, Frank Henenlotter was always one of my filmmaking heroes and it’s not just because he made the cult classic films Basket Case and Brain Damage. It was mainly because, like me, he was originally from Long Island, New York. In fact, I recall my best friend’s mother worked with Frank’s brother at the same police precinct and for whatever strange reason, this made my friends and I feel like he was the first director that we were two steps away from rather than someone we’d imagined being in the far away land of Hollywood. It proved to us you can make movies in New York and be someone from Long Island to make them too.

Growing up, Frank Henenlotter was always one of my filmmaking heroes and it’s not just because he made the cult classic films Basket Case and Brain Damage. It was mainly because, like me, he was originally from Long Island, New York. In fact, I recall my best friend’s mother worked with Frank’s brother at the same police precinct and for whatever strange reason, this made my friends and I feel like he was the first director that we were two steps away from rather than someone we’d imagined being in the far away land of Hollywood. It proved to us you can make movies in New York and be someone from Long Island to make them too.

So it’s funny how Frankenhooker, which would end up being my favorite of his films, was actually the last one I discovered. How I managed to go years without seeing it is completely beyond me, especially with the now legendary Bill Murray quote right on the front of the box stating “If you only see one movie this year it should be Frankenhooker.” Also, despite it’s location being set in New Jersey (in actuality, it’s Valley Stream), it’s arguably the most “Long Island” movie I’ve ever seen, at least in terms of reminding me what it was like growing up there in the late '80s/early '90s. For all of the above reasons I hold a special place in my heart for Frankenhooker.

Cry-Baby

If I had to sum up Cry-Baby in a sentence for someone, I would say that it is the wet dream of John Waters. Not since Kenneth Anger has there ever been someone who plays on the homoeroticism of hairless leather-daddies and rockabilly culture with such style. The movie also has what I would consider to be a dream cast for Waters, with Johnny Depp leading the pack. There's also his late muse, Ricki Lake, and small performances by Iggy Pop, Mink Stole, Joe Dallesandro, and a cameo by Willem Dafoe. To boot, the soundtrack is also outrageously good, featuring some of my favorite doo-wop, rockabilly, and psychobilly songs.

To compare this gem with other greaser vs. socs movies would be placing an emphasis on the more typical parts of the story; a nice town in 1950s suburbia is split in two, with its elite on one side and the trailer-trash on the other. But you have to remember that this is not The Outsiders or Grease, nor a jailhouse/Elvis flick. In fact, it's a parody of such movies. Waters takes the road-rebel genre and turns it into an opportunity to direct an over-the-top musical about teenagers and star-crossed love. The result is a story about a young man named Wade “Cry-Baby” Walker (Johnny Depp), a juvenile delinquent who prides himself on the ability to shed a single tear when confronted by his emotions. Behind him, sporting leather jackets with his name on the back, is his gang, referred to by the town as “drapes.” Perhaps the name comes from the emotional curtain of hair that keeps half of their faces in shadow. There's his plump and pregnant sister, Pepper (Ricki Lake); the fiery Wanda (Traci Lords); and the oddest couple to ever hit the screen, Milton (Darren E. Burrows) and his gal, Hatchet-Face (Kim McGuire). Their rivals on the playground are the suburban “squares,” and like other movies with the same theme, these characters are given little screen time and are presented as the enemy. The starlet among them is Allison (Amy Locane), a blonde who's seen as the most talented and beautiful among the rich. Allison and Cry-Baby lock eyes while getting a polio shot in the gymnasium. The sight of her makes him shed a tear, and the rest is history.

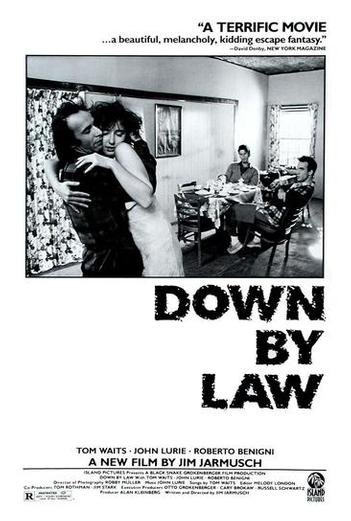

Continue ReadingDown by Law

"I am no criminal. I am a good egg. We are. We are a good egg."

"I am no criminal. I am a good egg. We are. We are a good egg."

—With this, the bouncing Roberto Benigni's "Bob" brings his two new friends together in Jim

Blue Velvet

Before director David Lynch got too carried away with his so-called genius, before his television show Twin Peaks brought him into the home and consciousness of the casually pretentious, before he would slap any old weird images together and have people call it art, back in ’86 he made his best film...Blue Velvet. It had much of the surreal oddball touches we’ve come to expect from a "David Lynch film," but instead of relying on hammy artifices, it’s just simply a haunting, funny, and beautifully crafted film. Though it’s challenging and can be considered an "art film," it’s still one of Lynch’s most accessible films and works just as well as a straight suspense movie.

Before Blue Velvet helped push David Lynch further into the "auteur" big leagues, he had already had some major artistic success. His first feature film, the horror, sci-fi, surreal Eraserhead became an instant cult film for both its disturbing imagery as well as the humor in its strange pacing. He got an Oscar nomination for his next film, the beautiful and disturbing studio picture, The Elephant Man. He was miscast as blockbuster director for Dune; the adaptation of the popular sci-fi novel was a massive bomb, both financially and creatively. Though Blue Velvet was produced by the big-time producing Dino De Laurentiis Company and was even originally sold as a mainstream thriller, it was Lynch’s return to his roots with an original screenplay, not developed for him, but by him and his own weird mind. Lynch and the film were obviously embraced by Hollywood. With Blue Velvet he would score another Oscar nomination for directing, but it meant he would never go back to being a "director for hire."

Continue ReadingFemale Trouble

Everyone told me that by the time I got into the early works of John Waters, I'd be blown away. Starting late in his career held its charm, especially with Cry-Baby and Serial Mom, but knowing that he was heavily inspired by the Kuchar brothers and cast eccentrics as wonderful as Divine did give their argument some weight. Female Trouble has not only become one of my favorite cult classics, but one that has helped me put the glorification of its many themes into perspective. On that level, the movie is way ahead of its time by approaching child abuse, violence, and habitual self-destruction as something inevitable and relevant to movie-goers. When you think about it, those issues are touched upon in the majority of American films, though, in retrospect, filmmakers don't often twist these observations into dark comedy.

Like all of his films, it's set in Baltimore, but stars his cream of the crop, Divine, and the wonderful Edith Massey. It's split into several chapters, the first being an introduction to Dawn Davenport's (Divine) youth in 1960. She and her best friends Chicklette and Concetta rant about how much their high school and parents suck and what they hope to get for Christmas. Dawn is expecting black cha-cha heels and vows to raise hell if her parents don't comply with her wishes. Christmas Day comes and she gets a pair of standard black shoes, causing her to throw her mother into the tree and disown her parents. She runs away and gets knocked up by a guy who picks her up hitchhiking (also played by Divine). With a new baby on her hands and him M.I.A., she begins her career as a stripper, prostitute, and petty thief.

Continue ReadingSins of the Fleshapoids

For those of you who do not know of Mike and George Kuchar, I highly recommend the documentary It Came From Kuchar which gives a thrilling account of their lives as underground filmmakers and artists. For those of you who know about them and are unable to find their work, I suggest looking at the releasing company Other Cinema, and the DVD compilations, Experiments in Terror. The documentary highlights their works, but three films stand out: The Devil's Cleavage, Born of the Wind, and Sins of the Fleshapoids. I was beyond thrilled to discover that some of their films were available for purchase, even if it's a just a few. The Other Cinema release of Fleshapoids also includes The Craven Sluck, and The Secret of Wendel Samson. Shot with consumer grade film with a cast of the director's friends, Fleshapoids is an experience in underground cinema that is not to be missed.

The Kuchars were at the tender age of 23 when they made this film, with Mike behind the camera and George in a starring role. The music assemblage and narration is done by Bob Cowan, and George Kuchar co-wrote the script. It takes place a million years in the future, where humans have enslaved androids with shells of human flesh, using them to do menial tasks and obey their every command. The earth suffered a nuclear war, turning rivers to poison and causing the near-death of all living things. The quest for scientific and mechanical knowledge brought about great turmoil, and now humans only indulge in the fulfillment of the senses. Picture hippies who wear mardi gras beads and fake furs. Their lairs are filled with leopard print, jewels, and bountiful displays of food. They call on the fleshapoids for massages and the ability to have everything done for them.

Continue ReadingCareful

Apparently there is something timeless about the Oedipus complex, as well as the fear of a catastrophic death. We play with the idea of the world coming to an end and cities crumbling to ruin in almost every action or sci-fi film. The thrill is exhausted, and the same is true of the over-saturated use of Freud. However, with Guy Maddin's Careful I venture to say that one may view a radiant and technically stunning movie about fear itself. The borders we create with other human beings, both relatives and strangers, are shifted in a way that is cult-like, similar to the backwards villages that were the foundation of our society. To add to the old feeling of a place filled with religious fanatics is a looming fear that is as outrageous as it is interesting.

In the town of Tolzbad, we find a group of people who must must never be careless or loud in their activities. In the past, the sound of an animal or a sneeze could potentially cause an avalanche from the mountains nearby. The fear of this tragic death has lead to several procedures and guidelines that should prevent it from ever happening again. Animals have had their vocal cords cut; children are gagged while playing until they are old enough to understand the consequences of their squeals; windows are covered with sheepskin, and all instruments are muffled. On top of the sound restraints are general warnings; never hold a baby by a pin, don't climb the mountains without proper gear, etc. The unison of superstition and nervousness provided more of an insight to a time long gone than the use of technicolor (or hand tinting?) throughout the film, or the silent-era design.

Continue ReadingGhost Dog: The Way of the Samurai

A contract killer (Whitaker), who lives his life in accordance with the “Hagakure: The Way of the Samurai,” becomes targeted by his mob bosses after a job goes wrong, leaving a witness behind.

Jim Jarmusch (Broken Flowers, Night on Earth) creates a film unlike any other with Ghost Dog. He manages to blend the coda of Kurisowa’s films about Feudal Japan with the characters and locales of an American mobster movie. In concept it may sound like the potential for a trainwreck, but in the hands of one of the leaders in independent cinema, it makes for truly original filmmaking. Jarmusch does a great job of utilizing this mixture of genres, not relying on cookie-cutter stereotypes, but rather, finding a way to flip everything on its head. The result is colorful characters that exist in a reality that is fresh and not found anywhere else.

Continue ReadingRadio On

There are multiple attitudes through which one can examine the film Radio On. It’s another example of the phenomenon of a film critic becoming a director. Christopher Petit was the editor for the film section of Time Out London from 1973 to 1978, and though he never achieved the notoriety of the Nouvelle Vague directors who once wrote for Cahiers du Cinema, his film career has turned out far better then Roger Ebert (who penned the script for Beyond the Valley of the Dolls) or Susan Sontag (who lost some of her critical credibility for the ill received Duet for Cannibals). Radio On is also a unique British-German coproduction, written and directed by an Englishman, but produced and shot by two Germans, Wim Wenders and Wenders’ ubiquitous cameraman Martin Schäffer. The art direction of the film is best compared to David Bowie’s album cover for Low, no coincidence considering Bowie’s “Heroes/Helden” is the song that starts the film. Actually, Radio On might one day be added to the list of films that will be better remembered for their soundtrack’s significance than the film’s cinematic merit. The film makes prominent use of hipster favorites like Kraftwerk, Ian Dury, and Devo, and includes a cameo from Sting in one of his first roles. Now Sting is not a hipster favorite, and probably never will be after boasting of his tantric exploits to multiple media outlets while promoting his adult contemporary hit “Desert Rose” in a slick Jaguar commercial. That doesn’t mean that we should forget Sting is a gifted actor, his performance in Brimstone & Treacle being a particular favorite.

It’s perfunctory to synopsize the plot in any film review, but here it seems somewhat irrelevant. A factory DJ drives to Bristol to investigate the mysterious death of his brother, but the plot is only a pretext for long periods of listening to the radio broadcasting the hip music and chaotic news reports of Northern Ireland bloodshed and conservative outrage that prevailed in Thatcherite England, as well as to look out the window at the excellently photographed landscapes. Once the DJ arrives in Bristol he becomes distracted by a German woman (Lisa Kreuzer) looking for her five-year-old daughter, Alice. This is a clumsy attempt by Wenders to expand the narrative of one of his own characters from his 1974 film Alice in the Cities, where Kreuzer plays a woman who abandons her daughter nine-year-old daughter of the same name. Wenders tries to create an impromptu prequel and belatedly illuminate the viewers of his previous film that Alice’s mother had once traveled to England to search for the child she would subsequently abandon. Considering Radio On is so sensitive to the politics and music of the decade it occupies, it was unwise of Wenders to ignore the glaring asynchronicity of Alice being five in 1980 and nine in 1974.

Continue ReadingBlack Snake Moan

Black Snake Moan opens in the deep, poor South, as “Ronnie” (Timmerlake) leaves to join the Coast Guard. He leaves, in his wake, his white trash girlfriend, “Rae” (Ricci) - a young woman of dubious morals. As soon as his bus has left, Rae falls under “the sickness” and spreads her legs all over the small town. She is left for dead in the middle of the rural countryside, and found by a God-fearing former blues man turned farmer named “Lazarus” (Jackson). He nurses her back to health, keeping her hostage in hopes of curing her wicked ways, with the help of the Lord. In her salvation from sin, he hopes it will also be his own.

This is truly a unique, bizarre, and well-crafted story about a very specific slice of life. Although it takes place in present day, the film feels almost like a work of the 1970s.

Continue Reading