Uzak (Distant)

Everyone’s paying homage to Tarkovsky nowadays, it seems, albeit often losing something in the translation. Turkish filmmaker Nuri Bilge Ceylan is among the few directors (along with Mauritanian Abderrahmane Sissako, Malian Souleymane Cissé and Iranian Abbas Kiarostami) who thankfully picks up not only on Tarkovsky’s aesthetic, but also his humanism and subtle humor.

Ceylan makes no attempts to hide his most obvious cinematic inspiration; using Bach in a library scene, referring to the Soviet director in a speech among artists, and in one scene even using one of the master’s films to bore his unsophisticated house guest into going to bed so that his host can watch porn in peace. In the special features, Ceylan also professes a debt, not surprisingly, to Anton Chekov and Yasujirō Ozu. A short film included on the DVD, Koza, is even more overt in its aspirations to reflect Tarkovsky.

Continue ReadingA Chinese Odyssey Part One - Pandora's Box

Not too long ago the DVDs for A Chinese Odyssey Parts One and Two came into Amoeba. From the brief once-over I gave the boxes, they looked like they might be interesting and worth checking out. Both starred Stephen Chow, they are Hong Kong fantasy films, and they were only $4.99 each. I wanted to do a little more research to see if they were worth my time and money and quickly made my way to the internets to see if I could find a trailer. Which of course I did. The trailer for Part One has fleeting glimpses of a half man/half monkey as well as a half man/half pig. People were flying across the sky, women were turning into spiders, and I think I even saw a giant bull. As I was watching this my reaction was a quiet, “Oh, this looks pretty good.”

…NO! What is wrong with me!? A movie about a half man/half monkey and his pig friend flying and fighting and doing magic cannot be described as looking "pretty good." It looks absolutely crazy is what it looks like! And this was the moment that I realized that I have truly gone off the cinematic deep end. Because I love Kung Fu movies. And I watch a lot of them. So much so that my brain can no longer recognize something like this as silly but instead as totally awesome…which it is.

Continue ReadingCarnival in the Night (Yami no carnival)

I'm starting to realize that, like certain record labels in music, film companies can also help steer you in the right direction when taking a chance on the unfamiliar. Besides the well-known Criterion restorations and releases of films held in high-esteem, Facets is another company that I'm beginning to see a great pattern with. I think it's safe to say that they deal with films that are a bit more obscure, which can sometimes mean taking a chance on something that you might hate. Carnival in the Night was not one of those cases.

Shot mostly in 16mm black and white with occasional transformations to color, the film is a visceral piece of art that should be applauded despite its subtle flaws. Using a documentary technique, director Masashi Yamamoto cast a small group of non-actors to more or less play themselves—each character linked to the sensational Kumi (Kumiki Ota). In the course of roughly 72 hours, you see the slums and residents of Shinjuku, Japan and Kumi's relation to them. Diving straight into the local punk scene, we see her band perform and you are immediately aware that this is a side of Japanese culture that you have never been exposed to.

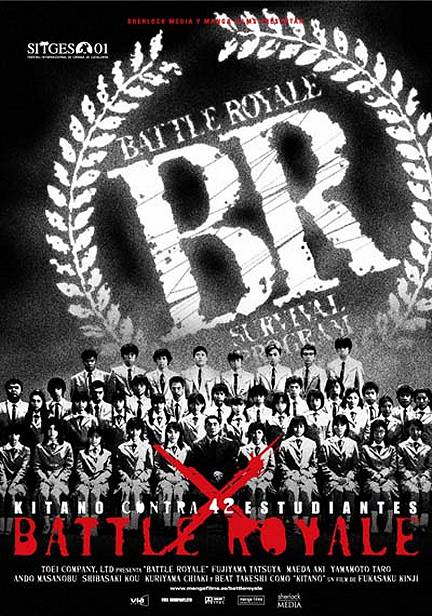

Continue ReadingBattle Royale

It's always quite special when you can see a film on the big screen for the first time. This was especially true of Kinji Fukasaku's Battle Royale, which, until its recent run at a revival theater here in L.A., had never been given a theatrical release in the U.S. The film is in the tradition of movies such as The Most Dangerous Game, Lord of the Flies, and Punishment Park—a series of circumstances unfold that places a group of people in a deserted space to either be hunted or turned into animals in captivity who must redefine “survival of the fittest.” Besides the ultra-violence laden with dark satire, the film is unique because those playing the game are a bunch of ninth graders from modern Japan, equipped with bizarre, sometime useless tools, and forced to kill each other or be killed by their own government. Even more bizarre is that the person to initiate them into the game is a former teacher, pushed to the edge by their insolence. The final flare comes in the form of two mysterious transfer students, each a willing participant in the hunt.

It's always quite special when you can see a film on the big screen for the first time. This was especially true of Kinji Fukasaku's Battle Royale, which, until its recent run at a revival theater here in L.A., had never been given a theatrical release in the U.S. The film is in the tradition of movies such as The Most Dangerous Game, Lord of the Flies, and Punishment Park—a series of circumstances unfold that places a group of people in a deserted space to either be hunted or turned into animals in captivity who must redefine “survival of the fittest.” Besides the ultra-violence laden with dark satire, the film is unique because those playing the game are a bunch of ninth graders from modern Japan, equipped with bizarre, sometime useless tools, and forced to kill each other or be killed by their own government. Even more bizarre is that the person to initiate them into the game is a former teacher, pushed to the edge by their insolence. The final flare comes in the form of two mysterious transfer students, each a willing participant in the hunt.

The story begins with an announcement about the new BR (Battle Royale) Act, in which students will be chosen at random to be pitted against each other due to their lack of respect for adults. This announcement is followed by a glimpse of reporters shoving to get a glimpse of a young girl, the latest survivor of a BR course. We then cut to a ninth grade class that's a bit more anarchic than usual. After writing on the chalkboard that they've decided to take the day off, Noriko (Aki Maeda), a kindhearted favorite in the class, approaches her befuddled teacher Mr. Kitano (Takeshi Kitano), seeking an explanation for the absence of her peers. Kitano exits without comment only to meet a ballsy student with a knife that slashes him. The teacher leaves the school and everything returns to normal for the most part. At the end of the year the school organizes a class trip in which everyone is loaded onto a bus for a retreat, including drop outs who've come back to school just for the field trip. The knifer is one of those students, and he is close friends with Shuya (Tatsuya Fujiwara), who recently lost his father to suicide. The students are thoroughly enjoying themselves, and Noriko even gathers up the courage to approach Shuya with a bundle of cookies she's baked just for him. Everyone takes a little nap and Shuya wakes to find his peers and teacher gassed while two menacing people wearing masks navigate the bus. Once he's found awake he is knocked unconscious.

Woman in the Dunes

Metaphors are perhaps the greatest and most poetic way to express a concept or condition without heavy exposition in dialog. A good poem, for example, should never be clear in words alone, but with a trained eye, one should and hopefully can decipher what the work is getting at. When I first saw Woman in the Dunes, while watching it and after finishing it, I interpreted it as having many metaphors, one being commitment and the surrender that comes to people in terms of settling down. Also, it places the main character into an alien existence that is far removed from his conventional and vanity-filled comfort zones. The sand in this film also presents a metaphor of its own, but I’ll leave that for you to conclude.

Early Japanese cinema is a leader in this kind of poetic and classic storytelling. Also shot in black and white, films like Double Suicide and Akira Kurosawa’s Rashômon incorporate centuries' worth of idealism and culture into an hour and a half’s worth of wonder.

Continue ReadingAll About Lily Chou-Chou

The youth of many nations, especially industrial ones, are full not only of angst but of a yearning to fit in and be understood. For Yûichi and a group of followers just like him, the "ethereal" music of Lily Chou-Chou has become the center of their world, both in cyberspace and reality. Yûichi is the fan site manager under the code name "philla," where he reviews and praises her music with a sense of enlightenment and desperation. Like today’s youth, only anonymous and without photos, these young people drift online in order to connect and rave about the things they find most interesting, which for this group is Lily. But underneath the melodies and enchantment, Yûichi and other fans are still just homeless souls looking for adventure. Though Yûichi is really just looking for an escape, his reality grants him the total opposite. He and his actual friends occupy themselves with petty theft, a mysterious summer vacation, and several humiliating pranks that go terribly wrong. His world shifts into a tumult of despair and unkindness in what he calls "the age of gray," where all the color bleeds dry from the world. His only solace is a lush and isolated rice field where he goes to be alone and listen to Lily.

This advancement of newfound responsibility and savage energy reminds me of what it is like to become an adult. When you’re young, you almost worship your music idols and look to their sound for understanding and piece of mind. But for Yûichi and others, the pressure to find that same balance in reality becomes nearly impossible after you reach a certain age. Not that some can’t or others never did, but for him there is no turning back or resolution.

Continue ReadingNight Catches Us

The low-budget period piece, Night Catches Us, is a rare kind of film these days - a complex, quiet, adult drama. More rare it’s about black people, and though it’s intense, the intensity comes from the characters' personal torment, not on-screen violence. In a perfect world Night Catches Us would catapult its first time feature director, Tanya Hamilton, as a major new relevant voice in film, but unfortunately there are no robots or superheroes in this story. The two lead performances by Anthony Mackie and Kerry Washington reaffirm their standing as two of the most reliable actors of their generation.

The low-budget period piece, Night Catches Us, is a rare kind of film these days - a complex, quiet, adult drama. More rare it’s about black people, and though it’s intense, the intensity comes from the characters' personal torment, not on-screen violence. In a perfect world Night Catches Us would catapult its first time feature director, Tanya Hamilton, as a major new relevant voice in film, but unfortunately there are no robots or superheroes in this story. The two lead performances by Anthony Mackie and Kerry Washington reaffirm their standing as two of the most reliable actors of their generation.

What happened to the “Movement” and how does that generation of black revolutionaries learn to live in a world after the revolution has fizzled out? The film slowly opens up and unfolds. It’s 1976, after years of being in exile as a snitch, ex-Black Panther Marcus Washington (Mackie) returns to his Philadelphia neighborhood to confront his past. The word on the street was that he got his best friend killed by the cops, which makes him an enemy to the folks in the hood, except that friend’s ex-wife Patricia Wilson (Washington). Also once a radical, she’s now a respectable lawyer raising a daughter as a single mother. She and Marcus seem to have something between them. Is that why her husband was killed? Or are they both just haunted by the death of a man and the loss of a way of life? What's left to fight for or stand for? These are two people lost in the past desperate to find a future. Though they do come together, there are too many ghosts between them to let them really fall in love, which in an Ibsen-like twist is what creates their bond.

Killer of Sheep: The Charles Burnett Collection

Killer of Sheep is a beautifully simple urban tale of an African-American community set in Los Angeles' Watts district during the1970s. Yes, the 1960s held a cultural revolution for racial freedom, but history often assures us that problems lie on far more complexities than just a cry for racial freedom. Every community has its individual fight and here we follow Stan, frustrated with the monotony of working at a slaughter house, and how it affects his life at home.

Noteworthy of the film is how personal it feels. It makes sense – Charles Burnett wrote, produced, shot, and directed it with a budget of less than $10,000 with the help of many close friends and family. The result is a natural, humanistic style. It takes a lot of courage for a director to let a story work inside out, and that's where the simplicity lies. Emotion is often wallpaper when complicated plots involve twists and turns. Instead, here, we are embraced in moments within relationships, moments of hardship, moments of tenderness, and moments of family-hood.

Continue ReadingRaisin in the Sun

"What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?"

Langston Hughes' opening lines to his poem "A Dream Deferred" inspires the title of the film, which is adapted from Lorraine Hansberry's 1951 Broadway play. The story is about the working-class African American family in Chicago, each member struggling against the idea of deferred dreams. The way each character has to fight against generational prejudice to achieve their dreams makes a most powerful, touching story, as deep to the core of African American history. And while I want to cry at the injustices that bind many to social despair, I am inspired by the moments of strength that the human spirit can possess.

Continue ReadingWatermelon Man

Godfrey Cambridge plays Jeff Gerber, a happy-go-lucky, casually racist and sexist insurance salesman who’s oblivious to the fact that nearly everyone that knows him finds him unpleasant and unlikeable. One morning he awakens to find, to his shock and repulsion, that he’s turned black in his sleep. He blames it on his daily devotion to his tanning bed but not even his doctor can explain it. As far fetched as it sounds, they try to explore the drastic change in Jeff's appearance in a fairly logical way. Of course, it ultimately can't be explained and the film moves into making humorous social commentary.

Some of the jokes are a bit formulaic. For example, his supposedly liberal wife is horrified at being married to someone who's turned black. Jeff stays indoors after his race switch until he works up the nerve to head to “the colored part of town” to buy some skin-lightening creams which (of course) fail to work.

Continue Reading