Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance

Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance is perhaps one of the best anti-hero films I have ever seen, based on concept alone. Chan-wook Park's Vengeance Trilogy is unlike most others because the plot, actors, and characters are all in no way linked or the same, but each film circulates around revenge. Ryu (Ha-kyun Shin) is a young deaf-mute who lives with his sister in a seedy apartment complex. His ambition was formerly focused on art school until his sister fell ill and needed a kidney transplant. He quit school and began working as a manual laborer in a factory in order to save up for her operation. Unable to give her one of his own kidneys because their blood types don't match, Ryu takes a chance and, using all the money that he has saved, tries to purchase a kidney from an illegal organ supply group which offers to give him the kidney he needs in exchange for one of his and 10 million won. But after waking up from the operation, he finds that the group has split with his clothes, money, and kidney.

Disheartened and furious about yet another streak of bad luck in his life, he vows to kill the people who wronged him. While visiting the medial center he frequents to find a donor, he receives the great news that they found a proper donor, which is hard to do in such a sort amount of time. The only problem is that Ryu has just been fired from his job and the operation costs 10 million won. Together, he and his girlfriend Cha-Yeong-mi (Doona Bae) decide to kill two birds with one stone by seeking vengeance on the illegal group and kidnapping his former employer's daughter for ransom in order to pay for his sister's operation.

Continue ReadingLate Bloomer (Osoi hito)

Picture, if you can, a film with the nightmarish quality of a Harmony Korine movie in Japanese, with a bit more focus on the characters and plot, that is deliberately presented as an avant-garde horror film. Late Bloomer is about as close to that combination as you're ever going to get. Not only is it toxic and arresting like the films of Korine, who I'll admit is one of my favorite directors, but the film is extremely off-putting.

As far as craft goes, it is shot in black and white (needed, I assume, for the eerie quality and mass bloodshed), with out-of-date dissolves and overlapping images that I haven't seen in years. The soundtrack is also jarring, mainly consisting of minimal electronic and death metal.

Continue ReadingTurtles Can Fly

Bahman Ghobadi, an Iranian director, is one who chooses to make a film about a subject matter that is not quite openly discussed today – in Turtles Can Fly, his impressive second directorial feature, he weaves a youthful tale set along the border between Iraq and Turkey.

The story follows a young boy, Satellite, nicknamed for installing television receivers in his minefield town of makeshift tents and tanks. He is part of a group of refugee children who expectantly await the war. This group of kids was placed in this area by Saddam Hussein and they find ways to work through Satellite’s leadership. In the midst of his tragedy, Satellite occupies himself with other duties – calling meetings, arranging work – essentially becoming the ringleader of the children. Among the children are the Boy With No Arms, and teenage girl Agrin, who accompanies a younger blind boy. The children’s fate, warranted by the end of the story, is a grim look at Kurdish experiences during the Iraq war and a collective of memories that don’t necessarily make any sense.

Continue ReadingZebraman

I know most folks immediately shy away when I say it’s directed by the maestro of mayhem, Takashi Miike (Ichi the Killer, Visitor Q, the Dead Or Alive series, Audition, and over 70 (!!!) other movies); and it’s finally being put out domestically by an outfit, foreign exploitation/ultra-gore distributors, Tokyo Shock Cinema, for which I have a soft spot in my ugly, mean heart, but Zebraman [or, more properly, “Zee-Borah-Mahnu”] quickly reveals itself to be super-campy fun and vaguely family-friendly (no disembowelment or graphic torture, honest!) in a way not seen from Miike since the uneven kiddie fantasy Great Yokai War or the gorgeous piece of art that is Bird People In China (one of the few films I can say without hesitation must be watched by everyone who loves movies).

Whereas Bird People made its pretentions obvious to all, Great Yokai War somewhat and Zebraman very explicitly are aimed (in the sense of appealing to AND in the weapon sense) directly at adults reared on monster/fantasy/superhero movies and television, making them terrific fare for dorks like me and you. C’mon, admit it, you know you are…

Continue ReadingLady Vengeance

"Everyone makes mistakes. But if you sin, you have to make atonement for it...Big atonement for big sins. Small atonement for small sins."

"Everyone makes mistakes. But if you sin, you have to make atonement for it...Big atonement for big sins. Small atonement for small sins."

—Geum-ja's (played by Yeong-ae Lee) words to her young daughter Jenny serve as an emotional lesson in morality from Chan-wook Park's 2005 Lady Vengeance.

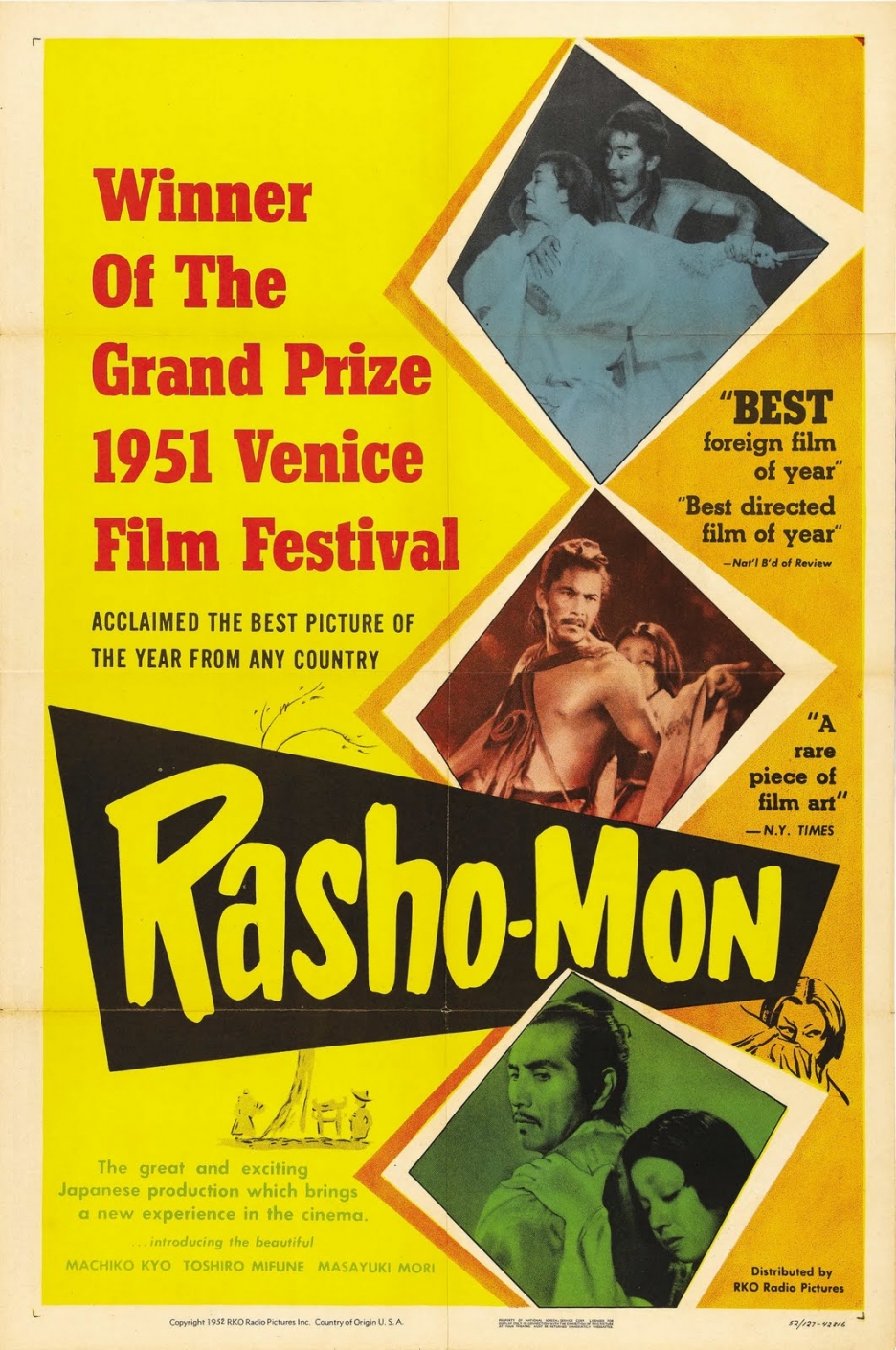

Rashomon

"It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves."

"It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves."

—The skeptical commoner's response to the conflicting testimonies sums up the plight of man in Akira Kurosawa's multilayered film.

When a Woman Ascends the Stairs

Regardless of the decade, there aren't many Japanese films that I've seen that approach the human experience on a more common level. The Japanese directors who've upheld great popularity abroad usually deal more with the folklore and customs of ancient Japan, while directors such as Takashi Miike (Audition, Ichi the Killer) and Kinji Fukasaku (Battle Royale) deal more with ultra-violence and action. Perhaps the most popular, Akira Kurosawa, has made an impact on the western world because American cinema, particularly Westerns, were of great influence.

While in Ginza, Naruse and his close acquaintances were gathered in a bar and noticed something special about the matrons. The complexity of their relationship with their customers, vastly different than the relationship of a geisha or bartender, had never been breached in cinema. Fueled by intentions to bring something new to the screen and introduce the world to the life of a high-end hostess, Naruse crafted this film. Its emphasis on the common man and his relation to the world was not exactly something that made it popular, and this, along with the director's other works, has left many bored, if not unsatisfied. Ozu's popularity with similar themes of the common man have done well, so what makes them different? Could it be because Naruse shot something in 1960 about people in 1960? Is it the lack of action in his films, or the fact that he cast based on a person's resemblance to the character in terms of personality? Whatever the reason, this film, while praised by cinefiles, has failed to impress or be understood by the masses; many have yet to realize that the film is full of feminist theory, breathtaking cinematography, and an example of the hardships that come with middle age.

Continue ReadingDolls

Takeshi Kitano’s directorial works are often separated into two strains where the considerable overlap is conveniently ignored in favor of an artificial dichotomy. On the one hand we have the explosively violent yet introspective crime dramas like Sonatine (ソナチネ), Hana-bi (花-火), and Boiling Point (3-4X10月). Less widely seen (and therefore wrongly characterized) are his quiet, contemplative mood-pieces like A Scene at the Sea (あの夏、いちばん静かな海), Kikujirō no Natsu (菊次郎の夏) and Kids Return (キッズ・リターン). Dolls is usually placed in the latter camp or as an anomaly as its mixture of familiar ingredients (watching the ocean, yakuza, explosive violence, stoic acceptance of tragedy) from both strains is impossible to ignore.

In the first story, Matsumoto spurns his girlfriend Sawako to marry another woman, at his parents’ insistence. Sawako loses both her mind and ability to take care of herself as a result. Matsumoto attempts to fix things by binding himself to her with a red cord. Together they wordlessly wander through stunning, artificial landscapes of amazing beauty steeped with sadness.

Continue ReadingBeshkempir

Beshkempir is a simple entwicklungsroman set in Bar-Boulak, Krygyzstan in 1960. It begins with a scene in which an infant is passed between women over a colorful rug. The women ritualistically intone, "This is not my son, this is not my son, but may his path in life be full of joy!" He is swaddled and placed into a cradle alongside a wooden bowl and a set of asiks (dice made from the knee bones of a lamb). They name him Beshkempir and he is taken in by a childless couple. From here on, we witness a world dominated by women and focused on children. The possible implication is that many of the Kyrgyz men died fighting for the Soviet Union in World War II. What few men are present usually are engaged in solitary activities like fishing or drinking vodka. The different generations of women seem to preserve the link to both the past and the future.

The film then jumps ahead 12 years to Beshkempir’s onset of puberty and is from here on is mostly shot in stark, poetic black & white. Beshkempir’s adoptive parents are strangely distant and reserved. Only his grandmother is openly affectionate. As a young man, Beshkempir’s attention is now divided between work, his friends and a burgeoning interest in the opposite sex. He and his friends eagerly spy on a woman bathing. Beshkempir and his best friend become interested in their neighbor, Aynura. Tempers flare and during a fight Beshkempir learns that he’s adopted. His father hits him for his role in the embarrassing situation and the boy runs away. He returns following a death in the family and is thrust further into adulthood as he is put in the position of settling the deceased’s earthly affairs.

Continue ReadingBlind Beast

A blind masseuse turns to sculpture when the thrill of touch becomes so tormenting that he needs an outlet for his desires. For every woman who he's ever worked on, there is an oversized replica of her limbs protruding from the walls of his studio. Of all the female clients that he and co-workers have massaged, Aki (Mako Midori) has always been an exceptional study in beauty. As the current muse of an avant guard artist, she exists only to be admired. Her figure becomes a target for Michio (Eiji Funakoshi), the blind sculptor, and with the help of his mother (Noriko Sengoku) he kidnaps the model with the hope of being able to immortalize her body in clay.

Michio and his mother live in a secluded warehouse far from Tokyo, and Aki is locked into his studio and given an ultimatum. She can either willingly model for his sculpture in captivity and be released upon its completion, or she can succumb to being put unconscious for the work until he's finished. He explains that for a blind person life is agony. The joys of the remaining senses are absent; they function only as a means of nourishment and necessity. Of these remaining senses, touch has become something that Michio needs to flourish. He further explains that he wishes to pioneer the art of touch, claiming that the other senses, such as sound, have an art form to match. Unwilling to accept things such as music to add substance to his life, he's hellbent on making the physical discovery of the human body a branch of art.

Continue Reading