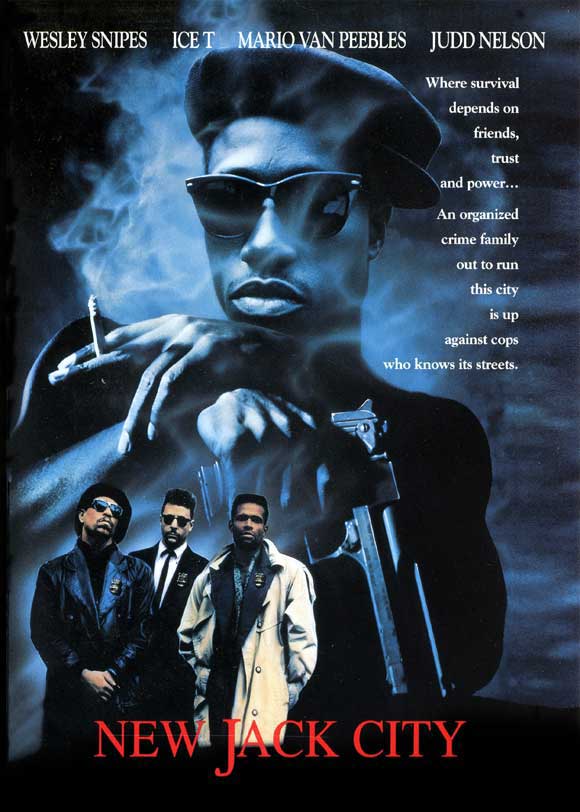

New Jack City

Going back all the way to the beginning of the talkies, the gangster flick, with its rise-and-fall narrative, has always been a dependable formula for Hollywood. And whether it’s Cagney or Pacino, the movies seem to have more fun with the “rise,” while the “fall” often feels like a tacked on message to mitigate how glamorous the first half may have seemed. The inner-city crime saga New Jack City is no different; though characters may take the high road and exclaim to the camera about how much the crack epidemic is ravishing the hood, really it’s an excuse to show the playas living large with their champagne in the pool, nifty guns, foxy ladies, and horribly colorful 1991 hip-hoppity fashions. And like so many gangster flicks before and since, New Jack City is a lot of fun and, as long as you don’t try to buy into its sermonizing, it holds up well as a cartoony period piece.

Going back all the way to the beginning of the talkies, the gangster flick, with its rise-and-fall narrative, has always been a dependable formula for Hollywood. And whether it’s Cagney or Pacino, the movies seem to have more fun with the “rise,” while the “fall” often feels like a tacked on message to mitigate how glamorous the first half may have seemed. The inner-city crime saga New Jack City is no different; though characters may take the high road and exclaim to the camera about how much the crack epidemic is ravishing the hood, really it’s an excuse to show the playas living large with their champagne in the pool, nifty guns, foxy ladies, and horribly colorful 1991 hip-hoppity fashions. And like so many gangster flicks before and since, New Jack City is a lot of fun and, as long as you don’t try to buy into its sermonizing, it holds up well as a cartoony period piece.

Here, the cops and dealers are showcased equally. For the good guys, you have undercover NY cop Scotty Appleton (rapper Ice-T, in his first lead acting role); he may be tough but he shows some heart to a junkie stick-up kid named Pookie, (comedian Chris Rock, in a rare dramatic performance that may’ve encouraged him to work on his stand-up more). Scotty helps him kick the dope after busting him. Meanwhile, on the other side of the tracks, dealer Nino Brown (Wesley Snipes) is able to enhance his business when he is introduced to a new cocaine concoction called “crack.” With his top lieutenants, Gee Money (Allen Payne) and Duh Duh Duh Man (Bill Nunn, Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing) they get the posse together (called the "Cash Money Brothers") and take over an apartment building, turning it into a successful crack assembly line and retail outlet.

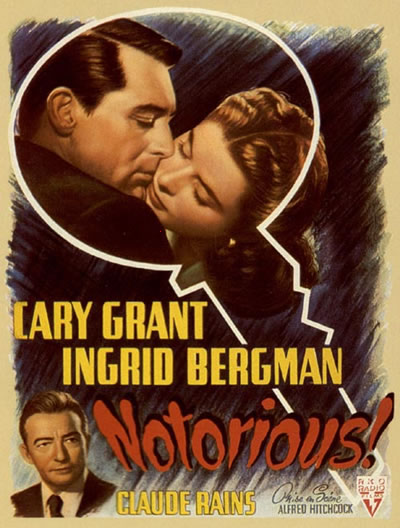

Notorious

The massive career of Alfred Hitchcock can be broken down into three sections. There’s his early British career (that includes both silent films and talkies) that ends with Jamaica Inn in 1939. Then there’s the first half of his American period; he crossed the ocean and found instant success with Rebecca and continued to hone his craft and try out different genres during the 1940s and early ‘50s. And then finally there’s his most celebrated period beginning around ’54 with Rear Window and Dial M for Murder, where the name Hitchcock became a brand and most of his films were events in themselves. Of that middle period, besides Rebecca there are a number of celebrated and still admired flicks including Spellbound, Shadow of a Doubt, and Strangers on a Train. But one film that really stands out, less flashy than the others but more emotionally devastating, is Notorious. On paper it’s an espionage thriller, but it’s actually one of the great heartbreaking love stories of the era.

The massive career of Alfred Hitchcock can be broken down into three sections. There’s his early British career (that includes both silent films and talkies) that ends with Jamaica Inn in 1939. Then there’s the first half of his American period; he crossed the ocean and found instant success with Rebecca and continued to hone his craft and try out different genres during the 1940s and early ‘50s. And then finally there’s his most celebrated period beginning around ’54 with Rear Window and Dial M for Murder, where the name Hitchcock became a brand and most of his films were events in themselves. Of that middle period, besides Rebecca there are a number of celebrated and still admired flicks including Spellbound, Shadow of a Doubt, and Strangers on a Train. But one film that really stands out, less flashy than the others but more emotionally devastating, is Notorious. On paper it’s an espionage thriller, but it’s actually one of the great heartbreaking love stories of the era.

Just after WWII, Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman), the party girl daughter of a convicted Nazi spy, is recruited by an American Intelligence agent, T. R. Devlin (Cary Grant), to prove her love to the red, white, & blue by infiltrating a group of Nazis who are hanging out in Brazil, planning a little postwar revenge against the USA. Things get complicated when, while waiting for the job to start, the two beautiful people fall in love. When the details arrive, it’s ugly; she has to go seduce an older ex-boyfriend, Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains), and find out what he and his cronies have in mind. She desperately wants Devlin to stand by and trust her; but though he does genuinely love her, he’s too cool to put down his guard and too professional to stop his bosses from deploying her. Still hoping to end up with Devlin, the dutiful Alicia takes the job and seduces Sebastian so well that he asks her to marry him, even while knowing she may be setting him up. It’s a love triangle, but in a twisted kind of knot that only Hitchcock could devise.

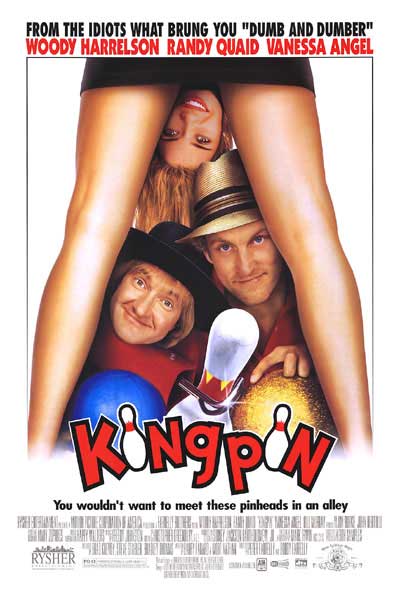

Kingpin

Though they hit the big-time as screenwriters and directors with their first film, Dumb & Dumber, the Farrelly brothers, Peter and Bobby, peaked commercially and critically with their third film, There’s Something about Mary. Their gross-out, dumb humor mixed with lazy sentiment became the standard for turn-of-the-century-era comedy; however, it was actually their less popular second film, Kingpin, which remains their best and funniest flick. It has the raunch, it has some heart, but most importantly, what makes the film special is the outstanding casting of its three leads: Woody Harrelson, Randy Quaid, and Bill Murray. Their performances, along with some of the supporting character actors, help the film rise above its sometimes weak script. Kingpin may not always bowl strikes but it is at least good enough to share a lane with the other best bowling movie ever, The Big Lebowski.

Though they hit the big-time as screenwriters and directors with their first film, Dumb & Dumber, the Farrelly brothers, Peter and Bobby, peaked commercially and critically with their third film, There’s Something about Mary. Their gross-out, dumb humor mixed with lazy sentiment became the standard for turn-of-the-century-era comedy; however, it was actually their less popular second film, Kingpin, which remains their best and funniest flick. It has the raunch, it has some heart, but most importantly, what makes the film special is the outstanding casting of its three leads: Woody Harrelson, Randy Quaid, and Bill Murray. Their performances, along with some of the supporting character actors, help the film rise above its sometimes weak script. Kingpin may not always bowl strikes but it is at least good enough to share a lane with the other best bowling movie ever, The Big Lebowski.

Back in the disco days of the late ‘70s, a young Iowan man, Roy Munson (Harrelson), looked like he was on his way to becoming a bowling god, until he hooked up with a conniving pro-bowler named Ernie McCracken (Murray) for a little hustling. The naive Roy didn’t realize that the sleazy Ernie, who drinks Tanqueray & Tab, was threatened by the younger bowler’s talent and leading him astray. A bad con with the wrong guys leads to Roy getting his hand cut off and the end to his promising bowling future. CUT TO: 17 years later. Roy now sports a prosthetic hand (over a hook) and a bad comb over haircut. He’s down and out, a drunk and bad conman forced to sleep with his hideously haggish landlady (Lin Shaye, brilliant) to cover his rent. Roy has hit the bottom until he happens upon a naive young Amish bowler, Ishmael Boorg (Quaid, the 40-something actor seems to be playing about 20). After much coercing and posing as an Amish cousin Roy finally convinces Ishmael to hit the bowling road with him to learn the con and eventually play for the big-time, where Ishmael can earn money to save the family farm.

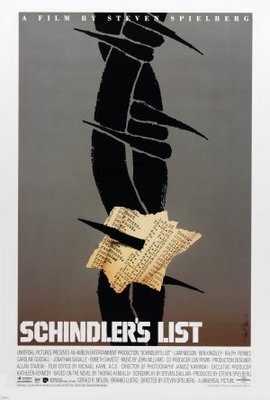

Schindler's List

Can a film’s reputation for high quality and moral weightiness make the act of watching it a daunting experience? Actually no, 20 years later, Schindler’s List may have a high-hatted standing as an important event film that must be seen because of some kind of personal solemnity, but like Citizen Kane, it may sound like drudgery, but Schindler’s List isn’t homework. And though the subject matter is utterly disturbing and even depressing, it’s so well made, so well acted and so well crafted that for this viewer, my most recent experience watching it was completely dazzling, not to mention absorbing and even entertaining. The film also gets some undeserved contempt and jeers because Mr. Blockbuster himself, Steven Spielberg, was the director. Some see it as an attempt at self-seriousness from a guy who has prided himself on his Peter Pan complex (even making the worst Peter Pan flick of all time, Hook), but why can’t the little boy grow up and evolve? Not since The Beatles put out “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band” has an artist’s evolutionary step been so massive. Back in 1993 Schindler’s List was screened during the Oscar friendly Christmas season, when just some months earlierSpielberg had released his live-action video game Jurassic Park. One film is a shallow CGI-created attempt at cheap thrills while the other is a painstakingly rendered and emotionally devastating nightmare. Dare I say it? No matter what you think or think you’ve heard Schindler’s List is a masterpiece, one of the best films of the last 25 years.

Can a film’s reputation for high quality and moral weightiness make the act of watching it a daunting experience? Actually no, 20 years later, Schindler’s List may have a high-hatted standing as an important event film that must be seen because of some kind of personal solemnity, but like Citizen Kane, it may sound like drudgery, but Schindler’s List isn’t homework. And though the subject matter is utterly disturbing and even depressing, it’s so well made, so well acted and so well crafted that for this viewer, my most recent experience watching it was completely dazzling, not to mention absorbing and even entertaining. The film also gets some undeserved contempt and jeers because Mr. Blockbuster himself, Steven Spielberg, was the director. Some see it as an attempt at self-seriousness from a guy who has prided himself on his Peter Pan complex (even making the worst Peter Pan flick of all time, Hook), but why can’t the little boy grow up and evolve? Not since The Beatles put out “Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band” has an artist’s evolutionary step been so massive. Back in 1993 Schindler’s List was screened during the Oscar friendly Christmas season, when just some months earlierSpielberg had released his live-action video game Jurassic Park. One film is a shallow CGI-created attempt at cheap thrills while the other is a painstakingly rendered and emotionally devastating nightmare. Dare I say it? No matter what you think or think you’ve heard Schindler’s List is a masterpiece, one of the best films of the last 25 years.

Though Spielberg made some truly great films:Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, and Raiders of the Lost Ark, all might be called pop-entertainment. His first forays into more adult-themed films were adaptations of great books by Alice Walker and J.G. Ballard; first, the overrated The Color Purple and then his underrated follow-up, the very good WWII Pacific prisoner of war flick Empire of the Sun. Meanwhile, he seemed to lose his magic, producing a lot of bad children’s television while his low points as a director included Always and Hook. And then ’93 happened; he re-found the mojo with his monster hit Jurassic Park and then his ultimate grown-up flick, the holocaust epic Schindler’s List.

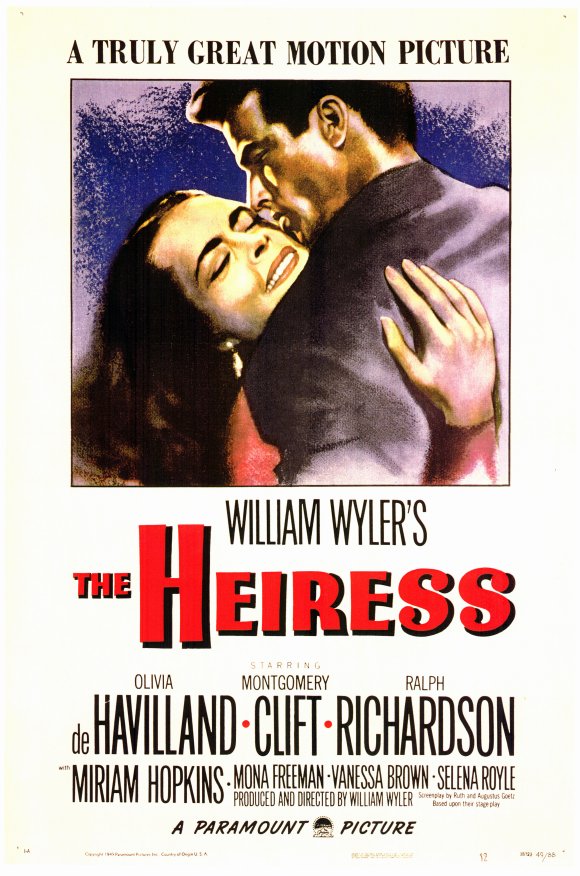

The Heiress

In some ways Olivia de Havilland may be one of the more underrated actresses of her generation. She wasn’t as iconic as some of her peers like Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis and not quite as beautiful as her rival sister, actress Joan Fontaine (Suspicion); instead of sexiness de Havilland brought a righteous intelligence to her roles. She was known throughout history mostly for playing Melanie in Gone with the Wind and for her association with the dashing actor Errol Flynn in their eight films together, most notably The Adventures of Robin Hood, They Died with Their Boots On, and Captain Blood. She had a number of other relevant roles in the ‘40s including The Snake Pit, Not as a Stranger, and Hold Back the Dawn. de Havilland won two Oscars: first, for the melodrama To Each His Own and then for her most interesting performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress, based on the Henry James novel Washington Square.

In some ways Olivia de Havilland may be one of the more underrated actresses of her generation. She wasn’t as iconic as some of her peers like Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis and not quite as beautiful as her rival sister, actress Joan Fontaine (Suspicion); instead of sexiness de Havilland brought a righteous intelligence to her roles. She was known throughout history mostly for playing Melanie in Gone with the Wind and for her association with the dashing actor Errol Flynn in their eight films together, most notably The Adventures of Robin Hood, They Died with Their Boots On, and Captain Blood. She had a number of other relevant roles in the ‘40s including The Snake Pit, Not as a Stranger, and Hold Back the Dawn. de Havilland won two Oscars: first, for the melodrama To Each His Own and then for her most interesting performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress, based on the Henry James novel Washington Square.

The late 1800s in New York City: mousy spinster Catherine Sloper (de Havilland) lives with her wise and widowed doctor father, Austin (Ralph Richardson who in real life was only 14-years-older than de Havilland), and her doting aunt, Lavinia (Miriam Hopkins). Catherine’s utterly plain and shy and unexceptional in every manner, which makes it more surprising when the handsome Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) shows up in town from California and immediately takes an interest in Catherine, wooing her with all his pretty-boy charms. Romanced for the first time, Catherine comes alive, becoming a giddy school girl utterly smitten with her suitor. The two lovebirds become engaged and plan to elope, but Austin doesn’t trust the rogue, knowing a playboy gold digger when he sees one; he tells Catherine he will disinherit her if she marries him. He also hurts his daughter when he coldly explains that Morris could have any young hottie in NY and why would he chose her if it’s not for the money? Proving Dad right, with the money not coming Morris doesn’t show up for the elopement and rushes back to California. Brokenhearted, Catherine realizes for the first time she really is a dullard who can only find love if she’s loaded with cash. And then to make matters worse, Austin dies and Catherine goes from a happy simpleton to a cold heiress. Years later Morris returns to try and get in on the money again, but the new self-empowered Catherine only pretends to buy into his oily trap and turns the tables on him instead, accepting a lifetime of loneliness to keep her dignity.

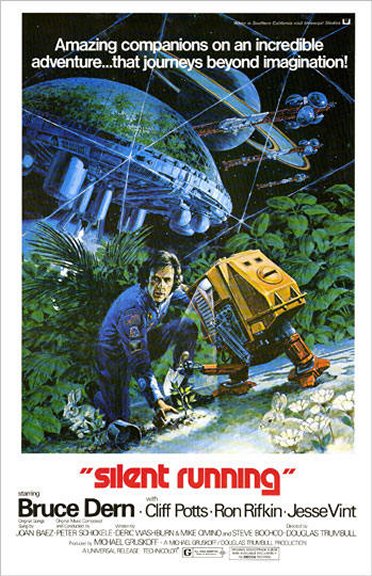

Silent Running

In the world of science fiction films Douglas Trumbull is quietly a hall of famer. His special photographic effects for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey would set the standard for outer space visuals for years to come (and I, for one, still find the models more effective than CGI). As a visual effects pioneer, Trumbull would also go on to lend his expertise on films ranging from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Towering Inferno, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Blade Runner, and, most recently, Tree of Life. As a director himself, he helmed two movies including Brainstorm in ’83, an interesting thriller about memory science, remembered mainly as Natalie Wood’s last film, and then, most importantly, the first film he directed: Silent Running, a sorta cerebral sci-fi environmentalist saga that has been a major influence on all the subsequent films of the genre.

In the world of science fiction films Douglas Trumbull is quietly a hall of famer. His special photographic effects for Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey would set the standard for outer space visuals for years to come (and I, for one, still find the models more effective than CGI). As a visual effects pioneer, Trumbull would also go on to lend his expertise on films ranging from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Towering Inferno, Star Trek: The Motion Picture, Blade Runner, and, most recently, Tree of Life. As a director himself, he helmed two movies including Brainstorm in ’83, an interesting thriller about memory science, remembered mainly as Natalie Wood’s last film, and then, most importantly, the first film he directed: Silent Running, a sorta cerebral sci-fi environmentalist saga that has been a major influence on all the subsequent films of the genre.

After all plant life has been destroyed on Earth, scientist and gardener Freeman Lowell (Bruce Dern) works aboard a giant space freighter called Valley Forge with greenhouse domes attached that hovers in space near Saturn, housing both extinct plant life and animals. The idea is that one day these space plant abodes will be able to return to Earth and repopulate its fauna. Lowell is the Adam of this wildlife Eden, aided by his three cute little robots: Huey, Dewey, and Louie, while his yahoo human shipmates (played by Ron Rifkin, Cliff Potts and Jesse Vint) get drunk and android around on their space go-carts with no sensitivity to what he is trying to cultivate.

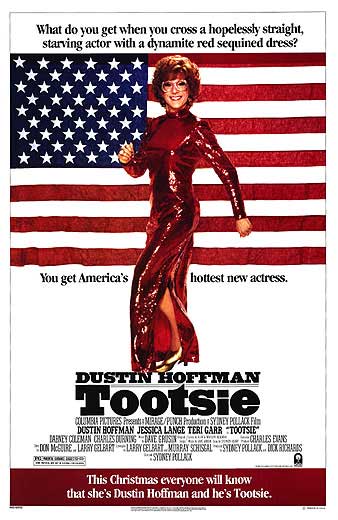

Tootsie

Even though it has a noticeably horrible Dave Grusin music score behind it (and even worse are the songs, giving it an icky, saccharin, early ‘80s vibe) Tootsie still manages to break conventions and has proved to be one of the best comedies of all time as well as the best film about the desperation of actors since Rosemary’s Baby. What at first can look like a gimmick, “Dustin Hoffman dresses up like a woman,” actually proves to be much more sophisticated; this isn’t a Some Like It Hot updating. With a screenplay by Murray Schisgal and Larry Gelbart (creator of M*A*S*H, the TV show and part of that group of young writers including Neil Simon, Carl Reiner, Woody Allen, and Mel Brooks who honed their skills on Your Show of Shows in the 1950s) Tootsie, like a Preston Sturges or Howard Hawks classic, is both a laugh-out-loud comedy and an insightful social examination. It may be clichéd but Hoffman’s character comes to understand being a man more from his life as an undercover woman. Fresh from the Women’s Lib era, Tootsie has a lot to say about gender roles and makes its statement cleanly.

Even though it has a noticeably horrible Dave Grusin music score behind it (and even worse are the songs, giving it an icky, saccharin, early ‘80s vibe) Tootsie still manages to break conventions and has proved to be one of the best comedies of all time as well as the best film about the desperation of actors since Rosemary’s Baby. What at first can look like a gimmick, “Dustin Hoffman dresses up like a woman,” actually proves to be much more sophisticated; this isn’t a Some Like It Hot updating. With a screenplay by Murray Schisgal and Larry Gelbart (creator of M*A*S*H, the TV show and part of that group of young writers including Neil Simon, Carl Reiner, Woody Allen, and Mel Brooks who honed their skills on Your Show of Shows in the 1950s) Tootsie, like a Preston Sturges or Howard Hawks classic, is both a laugh-out-loud comedy and an insightful social examination. It may be clichéd but Hoffman’s character comes to understand being a man more from his life as an undercover woman. Fresh from the Women’s Lib era, Tootsie has a lot to say about gender roles and makes its statement cleanly.

Struggling actor slash waiter, Michael Dorsey (Hoffman), teaches acting and coaches his friends’ auditions, but his exasperated agent (played wonderfully by director Sidney Pollack) lets him know, no one will hire him because he’s too much trouble (much like Hoffman’s own difficult reputation). After helping his needy actress friend Sandy (Teri Garr) prepare for a soap opera role, he ends up going up for it in drag and booking it, under his new stage name, Dorothy Michaels. With the help of his droll playwright roommate (an uncredited Bill Murray), keeping up his ruse as a woman becomes a fulltime job. He accidentally sleeps with Sandy, but falls in love with his soap costar Julie (Jessica Lange); she’s involved with the show’s chauvinist director (Dabney Coleman). On a weekend getaway Julie’s widower father (Charles Durning) falls for Dorothy as does her old cad costar John Van Horn (George Gaynes). Meanwhile on the set of the show Dorothy proves to be an actress who plays by her own rules, rewriting lines and following her instincts which make her an instant celebrity (I suppose once upon a time, soap operas had the ability to make their casts into names). Michael wants to put down his mask and reveal to everyone who he really is but besides ruining his now thriving career, it will complicate the relationships that he has made as Dorothy. He also begins to grasp how hard it is to be a woman in the 1980s.

The Wizard of Oz

There may not be another film more ingrained in Hollywood movie culture, more iconic, or more entertaining than The Wizard of Oz. For decades its yearly broadcasts on television become a rite of passage and, like a precious family heirloom, it was passed on; each year a new generation of children was introduced to it and eventually they grew up and did the same for their kids. As adults we’ve been able to find new aspects of it to be astounded by. For kids it’s also worked as the perfect portal to make a child into a more sophisticated movie watcher—after experiencing The Wizard of Oz it’s hard for a kid to go back to watching Barney. Their brains now need newer and richer material and of course there are so many films to follow it up with.The Wizard of Oz is also notable as a massive genre bender: besides succeeding as a family film, it’s a delightful musical, a dark Depression-era period drama, and it also works as a terrifying fantasy/ horror/ adventure flick. No matter what age, who couldn’t find something to love in it?

There may not be another film more ingrained in Hollywood movie culture, more iconic, or more entertaining than The Wizard of Oz. For decades its yearly broadcasts on television become a rite of passage and, like a precious family heirloom, it was passed on; each year a new generation of children was introduced to it and eventually they grew up and did the same for their kids. As adults we’ve been able to find new aspects of it to be astounded by. For kids it’s also worked as the perfect portal to make a child into a more sophisticated movie watcher—after experiencing The Wizard of Oz it’s hard for a kid to go back to watching Barney. Their brains now need newer and richer material and of course there are so many films to follow it up with.The Wizard of Oz is also notable as a massive genre bender: besides succeeding as a family film, it’s a delightful musical, a dark Depression-era period drama, and it also works as a terrifying fantasy/ horror/ adventure flick. No matter what age, who couldn’t find something to love in it?

For folks who may be reading this from another planet, here’s the basic set-up... In the gloomy black n’ white Kansas, young Dorothy Gale (17-year-old-ish Judy Garland, playing much younger) lives on her aunt and uncle’s farm with her beloved little mutt, Toto. A mean neighbor, Miss Gulch (Margaret Hamilton), threatens to have the pooch destroyed. So Dorothy escapes the farm with Toto, and while running away she meets a traveling fortune teller named Professor Marvel (Frank Morgan) who convinces her there’s no place like home. She gets back to the farm just as a tornado sweeps in, knocking her unconscious; she and her house are swept up into the air and land in a colorful place called Oz, inhabited by an army of little people known as Munchkins. It turns out her house landed on top of a witch, killing her, and leaving her still-living green sister, the Wicked Witch of the West (again, Hamilton), irate. Dorothy would be dead meat but as informed by another witch, this one kindly and beautiful, named Glinda (Billie Burke), the magic ruby slippers she is now in possession of will protect her. The Wicked Witch leaves swearing revenge. Dorothy is eager to get back to dullsville, Kansas, so before ditching her, Glinda suggests she follow the yellow brick road which will lead her straight to the brilliant Wizard who should know how to get her home.

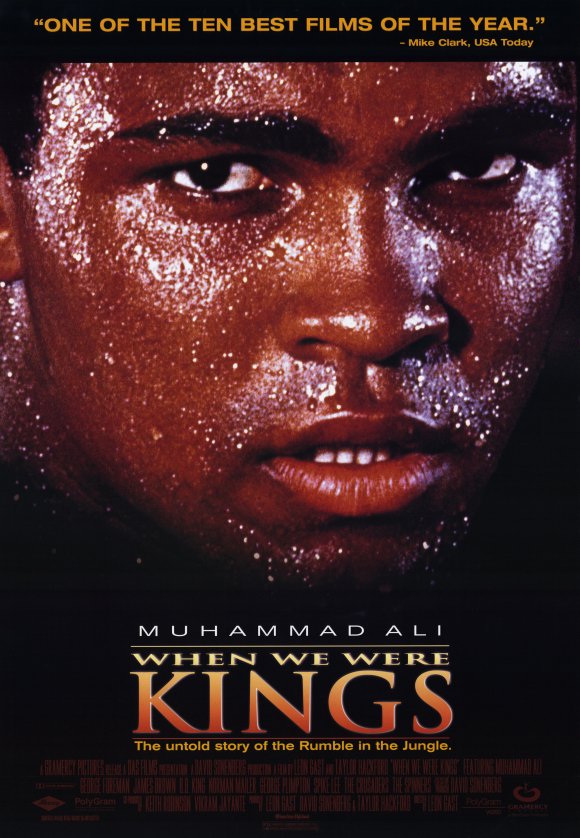

When We Were Kings

More than just a documentary about boxing or a boxer or a fight, Leon Gast’s astoundingly epic documentary When We Were Kings captures a fascinating period of history and tells the story of how a cocky young fighter named Cassius Clay became the worldwide icon known as Muhammad Ali. The biggest event in boxing history—and maybe the biggest event of the decade—was when boxing promoter Don King got the latest champ, the hard-hitting monster George Foreman, to take on the supposedly washed up 33-year-old ex-champ Ali in Zaire in ’74, in the event known as “the rumble in the jungle.”

More than just a documentary about boxing or a boxer or a fight, Leon Gast’s astoundingly epic documentary When We Were Kings captures a fascinating period of history and tells the story of how a cocky young fighter named Cassius Clay became the worldwide icon known as Muhammad Ali. The biggest event in boxing history—and maybe the biggest event of the decade—was when boxing promoter Don King got the latest champ, the hard-hitting monster George Foreman, to take on the supposedly washed up 33-year-old ex-champ Ali in Zaire in ’74, in the event known as “the rumble in the jungle.”

Ragtime

For Czech director Milos Forman, in that brief 10 year period between his two masterpieces, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus, he took on two monumental American mini-institutions as sources. Hair, his film version of the groovy stage musical about the Age of Aquarius, is mildly memorable, while Ragtime, his big adaptation of E.L Doctorow’s hugely popular and influential novel, was largely ignored in its day; but 20-something years later it holds up and now looks like one of the most overlooked historical dramas of the decade. Ragtime is a film about the small details and how little incidents can grow and change history and people’s lives. With a fascinating cast and some interesting, ahead-of-its-time politics, Ragtime is truly an original and entertaining movie.

For Czech director Milos Forman, in that brief 10 year period between his two masterpieces, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Amadeus, he took on two monumental American mini-institutions as sources. Hair, his film version of the groovy stage musical about the Age of Aquarius, is mildly memorable, while Ragtime, his big adaptation of E.L Doctorow’s hugely popular and influential novel, was largely ignored in its day; but 20-something years later it holds up and now looks like one of the most overlooked historical dramas of the decade. Ragtime is a film about the small details and how little incidents can grow and change history and people’s lives. With a fascinating cast and some interesting, ahead-of-its-time politics, Ragtime is truly an original and entertaining movie.

The film begins like the book: a sprawling story of scandal and trouble in the first decade of the 20th Century. It mixes real-life characters with fictional creations (similar to HBO’s Boardwalk Empire, the pulp work of James Ellroy, and countless books and films since). The famous murder trial of Harry Kendall Thaw (Robert Joy), who shot architect Stanford White (played well by overly macho writer Norman Mailer) over an affair with his wife, the showgirl Evelyn Nesbit (fresh out of Ordinary People, Elizabeth McGovern), dominates the first act. Meanwhile, a nice family just north of Manhattan in New Rochelle goes through massive changes. Mother (Mary Steenburgen) and Father (James Olson, an actor I wasn’t familiar with, who’s outstanding in this) try to keep their dignity while their Victorian values are constantly challenged. Her weird sibling, Younger Brother (Brad Dourif, less weird than usual, but still odd), works for Father at the fireworks factory and is obsessed with Evelyn, but she is too much the starlet for him. Meanwhile, Mother has taken in a black woman, Sarah (Debbie Allen), and her new baby. This is the thread plot that overtakes and dominates the story.