Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 1 ½

My most favorite movie titles: (1) Garfield 2: A Tale of Two Kitties & (2) Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take 1 ½, directed by William Greaves. Greaves’ title refers to the term “symbiotaxiplasm,” a concept coined by social philosopher Arthur Bentley. This term describes the assimilated totality of a society and its affects by humans and to humans. Every person, place, object, and thing that a society creates, maintains, and destroys is accounted for in the word symbiotaxiplasm.

Greaves added the “psycho” to affirm how our creativity and psychology can affect our society, and in turn, how we affect it. Make sense? Good. Moving on…

Continue ReadingAfrican American Lives

This is a great documentary that uses history, genealogy, and new technologies to retrace the violently and deliberately erased ancestral histories of a group of participants, all of African ancestry whose relatives were, for the most part, brought over involuntarily from Africa. The answers it provides are often thought-provoking in ways that most discussions about race aren't.

The host is Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr, a W.E.B. DuBois professor of the Humanities and the Chair of African and African-American Studies at Harvard University. I’d seen Gates in Wonders of the African World where he seemed to feign ignorance about everything he learned on his travels in Africa. I mean, he’s got some pretty big credentials and yet he’d continually act like he had no idea about the realities of his chosen subject of expertise until his interviewees revealed it to him. It seemed like he felt that pretending that everything was new to him would make him more identifiable to us, the presumably ignorant viewers. In this documentary, unfortunately, he does the same schtik which is just about the only shortcoming of the documentary, although it can be sort of funny. For example, he “guesses” that, given his appearance, his ancestors came from the East African kingdom of Nubia (huh?!), despite the fact that nearly all slaves in the U.S. came from the West Coast slave centers built centuries earlier, not by Europeans, but by other Africans. Of course it turns out that 0% of slaves were Nubian. His surprise at his DNA results seems genuine though when they reveal that his matrilineal line goes back to Ireland.

Continue ReadingExtreme Private Eros: Love Song 1974

Ever wish you could meet a strong-willed Japanese feminist from the '70s? Now's your chance. Director Kazuo Hara introduces us to a woman named Miyuki Takeda—his former lover, and one of the most impressive subjects to ever be captured on film. After leaving him and taking their child to travel from mainland Japan to Okinawa, Hara decides that the only way to stay connected with her and understand what happened in their relationship is to document her and those who enter her life after their time together. So from 1972 to 1974, Hara frequents Okinawa to film her, doing so with grace and capturing some amazing footage of locals as well.

In 1972, Miyuki begins a new relationship with a woman named Sugako. His presence throughout this segment caused tension and unease with the couple as their disoriented and sometimes abusive relationship unfolds onscreen. In this section of the documentary we are able to see an enormous transformation with Miyuki. Not only has she decided to abandon all aspects of her personality that would classify her as a "good wife," but also everything and anything that could prevent her or her son from becoming anything short of radical.

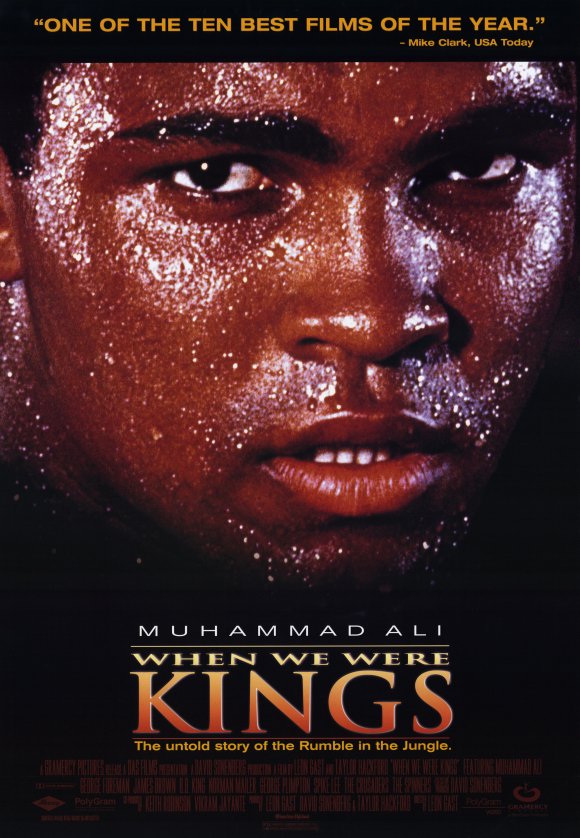

Continue ReadingWhen We Were Kings

More than just a documentary about boxing or a boxer or a fight, Leon Gast’s astoundingly epic documentary When We Were Kings captures a fascinating period of history and tells the story of how a cocky young fighter named Cassius Clay became the worldwide icon known as Muhammad Ali. The biggest event in boxing history—and maybe the biggest event of the decade—was when boxing promoter Don King got the latest champ, the hard-hitting monster George Foreman, to take on the supposedly washed up 33-year-old ex-champ Ali in Zaire in ’74, in the event known as “the rumble in the jungle.”

More than just a documentary about boxing or a boxer or a fight, Leon Gast’s astoundingly epic documentary When We Were Kings captures a fascinating period of history and tells the story of how a cocky young fighter named Cassius Clay became the worldwide icon known as Muhammad Ali. The biggest event in boxing history—and maybe the biggest event of the decade—was when boxing promoter Don King got the latest champ, the hard-hitting monster George Foreman, to take on the supposedly washed up 33-year-old ex-champ Ali in Zaire in ’74, in the event known as “the rumble in the jungle.”

La Commune (Paris, 1871)

If there’s one thing the French government doesn’t want people to know about, it’s that for two months Paris was a Socialist state ruled independently from the rest of France. Napoleon III’s catastrophic decision in 1870 to declare war on Prussia for amorphous reasons of power and prestige precipitated France’s ruinous capitulation to the Prussian army, ultimately concluding in a Prussian assault on the capitol. During the siege, working class Parisians suffered the most, falling into destitution as prices of essential goods rose, and becoming increasingly resentful of the seemingly immune bourgeoisie. The government moved to Versailles during the war and, after Napoleon III died in battle, set up a new conservative Republic there. At the end of the siege, the army tried to re-appropriate cannons originally left behind to protect the city from the invading Prussians, which Versailles now worried would fall into the control of anarchist elements of the restless populace. However, Parisians protested the removal of the cannons because they had been paid for with public funds, and the listless soldiers, identifying more with the howling mob than with their well-bred officers, fraternized with the crowd and refused to take the cannon. Revolutionary spirit inflamed the city and La Commune was born. Without outside assistance, regular Parisians set up elections, formed a government with executive and legislative branches, and outfitted a defensive army. The citizens of the Commune created worker owned co-operatives, passed a law separating church and state, and abolished religious schools in favor of secular state education. In two months it was gone.

Director Peter Watkins takes five hours and forty-five minutes to narrate not only the rise and fall of the Commune, but also the inspiration and contradiction at the core of all its ideological rhetoric. Shot on black and white 16mm film in a warehouse in the suburbs of Paris, Watkins recruited non-professional actors to play characters that they could politically sympathize with and then asked them to research the period in detail. He also shot the scenes in chronological order for the benefit of the actors, an almost complete rarity in filmmaking. As a result, the line is blurred between fiction and documentary, and historical re-enactment is enriched by real people devoting themselves to the period doppelgängers they have created. The film is meticulously careful to be historically accurate, portraying without hesitation the shortcomings and shortsightedness of the Commune, as well as their fair-minded and progressive principles. There is, however, one intentional anachronism: television. Commune TV is the television of “la peuple” and Versailles TV is the propagandist station of the establishment. The government station with its preening, self-serious anchors and cliché theme music intros is far and away the highlight of the film.

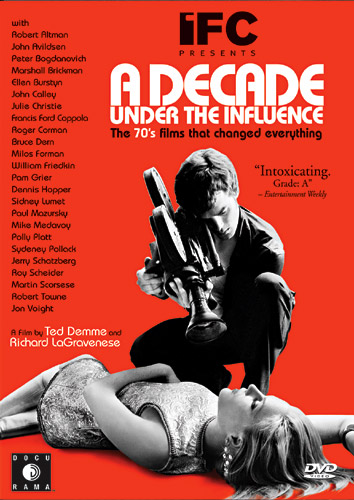

Continue ReadingA Decade Under the Influence

Playing on the title of the groundbreaking John Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence, or maybe ’70s cokehead producer Julia Phillips’s memoir Driving Under the Affluence, the IFC-produced, three-part documentary A Decade Under the Influence is a fawning but wildly entertaining tribute to the films of the ’70s (actually 1967 onwards) and the maverick filmmakers who reinvented Hollywood. It’s the perfect film companion to Peter Biskind's incredibly readable book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which also spawned a BBC-produced documentary with the same name. The IFC series may come out slightly on top if only because it’s an hour longer and, at just 119 minutes, the BBC flick may not cover enough ground, while A Decade Under the Influence is crammed wall to wall with clips and interviews. For anyone who romanticizes this era in film (like me) this is three hours of pure, giddy love.

Playing on the title of the groundbreaking John Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence, or maybe ’70s cokehead producer Julia Phillips’s memoir Driving Under the Affluence, the IFC-produced, three-part documentary A Decade Under the Influence is a fawning but wildly entertaining tribute to the films of the ’70s (actually 1967 onwards) and the maverick filmmakers who reinvented Hollywood. It’s the perfect film companion to Peter Biskind's incredibly readable book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which also spawned a BBC-produced documentary with the same name. The IFC series may come out slightly on top if only because it’s an hour longer and, at just 119 minutes, the BBC flick may not cover enough ground, while A Decade Under the Influence is crammed wall to wall with clips and interviews. For anyone who romanticizes this era in film (like me) this is three hours of pure, giddy love.

Episode One: Influences and Independents, begins with the big gaudy premiere of the crappy big gaudy musical Hello Dolly in ’69; the thesis: that bomb marked the end of the studio era. An intelligent group of interviewees, including Francis Ford Coppola, Dennis Hopper, and William Friedkin, give us the set up: the civil rights movement, Vietnam War, the women's movement, ’60s innovative rock & roll and later Watergate, the formation of the counter culture, and youth movement had a generation of people asking why and breaking the rules. For filmmakers who were seeing the art house foreign films of Godard, Kurosawa, Truffaut, Antonioni, Bergman, and Fellini (and of course Julie Christie throws in the working class films of early ’60s England) the current beach flicks, musicals, and romantic comedies of Hollywood no longer seemed relevant. When Arthur Penn took influence from the French New Wave (who were influenced by American film noir and gangster flicks) and came up with his sexually frank and violent Bonnie and Clyde, it opened the floodgates for a new kind of American film. With Roger Corman and BBS (Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider, and Steve Blauner) creating a new class of filmmakers who could work cheap while learning their trade and John Cassavetes making his homemade indie movies, the idea for the “’70s flick” was solidified. Those early influential flicks of the era are recalled and analyzed, including Easy Rider, Targets, Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, and The Last Picture Show. But it’s not all classics; less memorable movies like Joe and Hi, Mom! are also included and even Dirty Harry is given props as an obvious influence.

I Think We're Alone Now

You've always heard stories of stalkers and people who honestly believe that they are seriously destined to be with certain celebrities. In a sense, our culture has encouraged such activities. Since the beginning of the film industry and, in the last century with musicians, celebrities in the performing arts have been followed by paparazzi and fans with little escape from the public eye. In almost every grocer there are magazines filled with false or accurate news of some star. The biggest market seems to be teen magazines and their readers who can become more involved by sending in fan mail, etc. This kind of activity eventually fades and these young people stop being fixated. I Think We're Alone Now follows two individuals who became obsessed with a singer way past their youths, and despite their oddness, quite organically.

Tiffany Darwish, referred to as simply Tiffany, had a singing career in the '80s and was a pop icon, though her popularity fizzled out within a few years. Some of her songs still receive radio play and are known by just about everybody. The title of this documentary shares the name of perhaps her most popular song, a cover of Tommy James & The Shondells, and one that is of great importance to one of the subjects in the film.

Continue ReadingPatti Smith: Dream Of Life

OH TO DREAM... Patti Smith: Dream Of Life falls in the realm of documentary, I suppose, but really I'd like to call it a "musical document" for the sake of this writing and my own personal flare for "adjectivery." I never would have "dreamed" I would be into a film about Patti Smith [it's true]. For whatever reason she had never really made a blip on my radar outside of her popularized "G-L-O-R-I-A."

INWARDS & INNARDS Wandering around a room partially full of keepsakes and other remnants we find Patti Smith, a curious soul. She states that this film has been in the works for 10 years and that she will not be leaving this room until the film is completed. What follows is a series of explanations and events exploring her inner workings and outer experiences [family, death, art, friends, politics], all obvious, subtle and having an underlying strange honesty to them that seems clearly unique to her. I was impressed. She talks to us about certain objects in the room as if recreating some kind of "show and tell" experience from childhood. Books, photographs, a guitar Bob Dylan once played, her son's baby clothes, her own childhood dress, Robert Mapplethorpe's ashes, artifacts, all surrounding her as she builds a cluttered memory chamber. She brings more into the room throughout the duration. It touches the semi-sweet sadness inside.

Continue ReadingGirl 27

Though this documentary has a subject that is extremely compelling and brave, it was unfortunately poorly made. Somehow I don't believe that the fault was at the hands of the directors or producers, but simply the lack of cooperation and substantial footage. The fact that I still took away a lot of information and was able to truly sympathize with all the victims and their stories was enough to make me see the film as something well-worth everyone's time.

In April 2003, Vanity Fair printed their Hollywood Issue. Inside was a story titled, “It Happened One Night...at MGM,” which gave a detailed account of a massive cover up by MGM that has to do with the rape of Patricia Douglas. In 1937, MGM decided to organize a large convention for all of its sales employees and producers who, I should add, were all men. These conventions were seen as a sort of holiday among the participants, where lodging, food, entertainment, and a lot of alcohol were provided to ensure that everyone had a good time and felt that they were essential to the company. The entertainment for one of these conventions would come in the form of over one hundred female dancers, most of whom were under-aged girls. Before the big party of the convention happened, a casting call was made by MGM in which these girls were told that they would be dancing in a movie and needed to be fitted for cowgirl costumes, then report to a barn on Hal Roach's ranch. On the casting call list, one of these girls had her name in bold and underlined: Girl 27, Pat Douglas, who was 17 at the time. The movie the girls were supposed to be dancing in turned out to be a stag party for all of the MGM employees, one of whom was presumably made to feel as though he had one of the many girls all to himself. That man was producer David Ross and the girl he was pushed toward was Patricia Douglas.

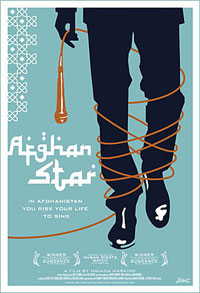

Continue ReadingAfghan Star

Who would have guessed that an American Idol type of singing competition show could bring enlightenment, democracy and change to a nation? Of course not in the U.S. - our version only inspires cruelty and insipid syrupy belted versions of stale Whitney Houston songs. But in Afghanistan, their version of the show, Afghan Star, may just be dragging a country that has been plagued by decades of wars, poverty and tribal fighting into the twentieth century where everyone believes that becoming famous is the goal of life.

Who would have guessed that an American Idol type of singing competition show could bring enlightenment, democracy and change to a nation? Of course not in the U.S. - our version only inspires cruelty and insipid syrupy belted versions of stale Whitney Houston songs. But in Afghanistan, their version of the show, Afghan Star, may just be dragging a country that has been plagued by decades of wars, poverty and tribal fighting into the twentieth century where everyone believes that becoming famous is the goal of life.

Directed by Havana Marking, the documentary Afghan Star is the most fascinating peak into Middle Eastern media since Control Room five years earlier. Here we follow four contestants, each with different ethnicities from different parts of the country who risk their lives to sing on television. If you think the divisions of the States or regions in U.S. can be tense, Afghanistan's animosity between neighbors keeps the country constantly on the brink of a mini-civil war. But after years of Taliban repression (where television and singing were banned) and still a strong conservative Muslim arm in the country, the contestants and the show’s producer/host Daoud Sediqi are convinced that what their country needs is music and they are eager to give it. Even having a woman sing on TV is still considered radical and leads to a number of dangerous incidents which are well covered in the documentary. The film also does a great job of humanizing the Afghan people who show that no matter how dire the country seems to be, the contestants and the show's audience (at least a third of the country are regular watchers) are still so full of hope. On Afghan Star the theme songs from The Sound Of Music and Footloose are still alive, playing out with life and death consequences.