Hud

Antihero. The character you are suppose to be rooting for but find his actions unheroic. Today it’s commonplace in films and fiction. In 1963, the only antiheroes were usual gritty private eyes in dime store novels or gangsters. Then came Paul Newman as Hud. He represents the end of the old cattle ranchers era. It’s a battle of wills with his aging proud father for the soul of his innocent nephew and for the ethics that the family will use in its business dealings. You want to root for Hud. He’s so cool, its megastar, Paul Newman. He has moments of vulnerability when you can see why his heart is so hard. But by the end his selfishness and amoral nature make him so unlikeable. It also makes for an amazing story.

In Paul Newman’s monster-sized career, perhaps only Bogart, Nicholson and maybe James Stewart have ended up with so many iconic roles. As far as performances go, Newman was always good; the consensus would say that his performance as the broken down, drunken lawyer in The Verdict is his masterpiece. I would nominate Hud for second place on his Hall Of Fame chart. And that is saying a lot, with so many other important roles to chose from: The Hustler, Cool Hand Luke, The Color Of Money, Nobody’s Fool and the underrated Hombre to name a few, were all fantastic. Not to mention the crowd pleasers like The Sting and Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid which are beloved by many.

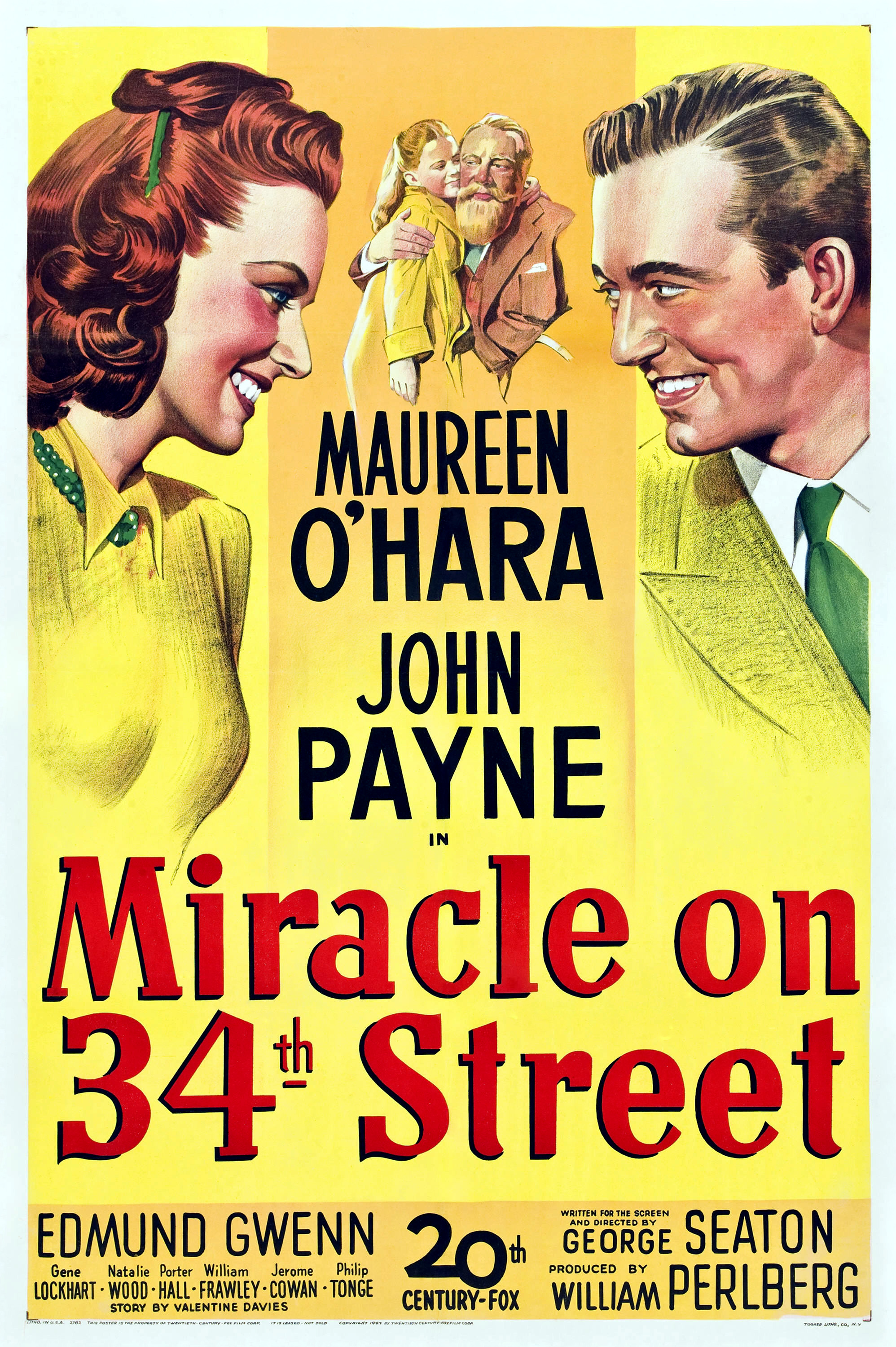

Continue ReadingMiracle on 34th Street

No other film in history has been able to capture the spirit of Christmas and toss cinders on the commercialism that the holiday has come to represent quite like Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street. At 60-something-years-old, the film is still just as relevant, funny, and, ultimately, moving as it ever was. Like How the Grinch Stole Christmas (the original animated version), It’s a Wonderful Life,and the more recent A Christmas Story, Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has become standard, even compulsive, viewing during the holiday season. Today’s kids may think that Christmas is some kind of video game or a season to shop and spend money, but Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has reminded generations what it’s supposed to be about. As Mr. Kringle says in the film, “Christmas isn’t just a day; it’s a frame of mind.”

No other film in history has been able to capture the spirit of Christmas and toss cinders on the commercialism that the holiday has come to represent quite like Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street. At 60-something-years-old, the film is still just as relevant, funny, and, ultimately, moving as it ever was. Like How the Grinch Stole Christmas (the original animated version), It’s a Wonderful Life,and the more recent A Christmas Story, Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has become standard, even compulsive, viewing during the holiday season. Today’s kids may think that Christmas is some kind of video game or a season to shop and spend money, but Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has reminded generations what it’s supposed to be about. As Mr. Kringle says in the film, “Christmas isn’t just a day; it’s a frame of mind.”

The beautiful but icy Doris Walker (Maureen O’Hara) is a cynical single mom who works for the glamorous Macy’s Department Store in New York City. While handling the big Thanksgiving Day Parade she pulls a bearded old man (Edmund Gwenn) off the street to play Santa Claus. The twist is he actually claims to be the jolly toy maker and even calls himself Kris Kringle. The good-natured, but possibly delusional, old coot is so convincing Macy’s hires him to be their full-time in-store Santa. Meanwhile, Doris’s daughter, Susan (Natalie Wood), is her mom’s mini-me, with equal disdain for childish things like make-believe. But when she befriends her do-gooder neighbor, a bachelor lawyer with the unfortunate name of Fred Gailey (John Payne), he encourages her to start to act like a kid and gets Doris to instantly open her heart to romance. All three befriend Kris, while he and Fred try to loosen up the two uptight females. Little Susan is taken aback when she see Kris speak Dutch to a peewee foreign girl, giving her the idea that maybe this guy is the real deal.

The Big Knife

I get a real kick out certain big, strapping, "man's man" actors: Heston, Mitchum, Lancaster, Hayden and, most importantly, Jack Palance. Palance could work his way through those 50s monologues of seine-styled verbiage like Rosalind Russell on meth. If the modern-day film audience has trouble with his histrionic delivery, it’s surely because of the contemporary bias for realism within acting. To me, he's like the artist who manages to find the perfect curved line when representing action. Cartoonish? Maybe, but any comic book fan can tell you about the pleasure of a broad stroke. I prefer to look at that old-style melodramatic acting in which Palance excelled as the representation laid bare, a modernist nod to the fact that what's going on isn't real, but the emotions and thoughts are. He is the brutal signifier. And he was never better than in Aldrich's The Big Knife, a more masochistic film pleasure you’ll not likely find. The script is by James Poe, based on the play of the same name by Clifford Odets, whose work, when properly adapted as it is here, makes the more famous Tennessee Williams adaptations look like Sundance productions.

Palance plays a big-time Hollywood actor who's had his dreams replaced, piece by piece, with factory-line assembled product. Unfortunately for him, he knows what art is, but the Factory, in the body of Rod Steiger (one of the few actors who could go toe-to-toe with Palance up the tower of babble), has something on the actor, namely that he killed a child while driving drunk. Palance makes too much money for Steiger's hack producer, so he's forced to sign another 7-year contract of servitude. Due to his infidelity to both his art and their relationship, the actor’s wife, played by noir-babe Ida Lupino, is living separate from him with their child, and has threatened to leave for good if he signs on again. The misery becomes even more turbid when, like a pig to mud, Shelly Winters, playing the girl who was with Palance on that drunken night, threatens to reveal his dirty secret to the gossip columns. Steiger, not wanting to lose his golden goose, tries to get Palance to help kill Winters. The screen threatens to implode each time Palance and Steiger take a breath before launching into another tirade. With the aid of a bunch of booze, a lascivious harpy draining Palance's moral center (played by barrel-browed Jean Hagen), and a whole slew of master-servant dialectics between the royalty (Palance, Steiger) and their hanger-ons (the great character actors Everett Sloane and Wesley Addy, among others), the film reaches its moribund conclusion.

Continue ReadingEast Of Eden

Just scratching the surface of John Steinbeck's massive novel, the film version of East Of Eden is most important as a introduction to James Dean and as another notch in director Elia Kazan's impressive film belt. Though the story can be a little melodramatic, concentrating on two brothers - one good, Aron (Richard Davalos), and one bad, Cal (Dean) - and and their relationship to their father, Adam (Raymond Massey) during the WWI years in Salinas, California. Adam is an overly moral man while the boy's mother Kate (Jo Van Fleet) is a brothel owner. If the biblical good and evil imagery sounds heavy-handed, it is, but for James Dean's fascinating performance the film's soapy elements are well worth slogging through. With only three films before his death at the age of 24, Dean's impact on film and film acting cannot be understated. Early in the decade Dean worked as a film extra in Hollywood, before moving to New York, where he began studying with famed acting guru Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio, like his idols Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando before him. He made some minor noise working on the stage and on live television, before he was plucked up by Kazan for the role that would make him an instant star and begin an iconic legend that still continues almost 60 years after his death. As the moody Cal, Dean uses every kind of slump and mumble known to man. In the first half of the film, as he seeks to reconnect with his long lost mother, he always looks like he is going to tumble over, as if he's walking on his tip-toes. His face always seems on the brink of tears. Later, his character gains some confidence and seems to have a stronger control of his body until, after one last grasp at connecting with his father, rejected, he flips out and goes into histrionics (as do the camera angles). Dean wear...

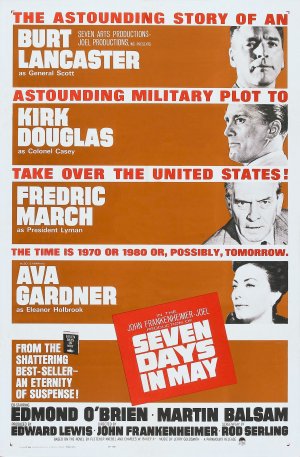

Continue ReadingSeven Days in May

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

Based on a novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey, Douglas plays Colonel Martin "Jiggs" Casey, a Pentagon Joint Chiefs of Staff aide to the powerful James Mattoon Scott (Lancaster). Jiggs is a moderate, more devoted to upholding the Constitution than playing politics, but the guys above him are stone-cold hawks and don’t like it when liberal President Jordan Lyman (Fredric March) signs a nuclear disarmament agreement with the Soviets. Reading cables, hearing secondhand conversations, and finding an incriminating crumpled note leads Jiggs to deduce that Scott is planning a military coup against The White House. He takes his suspicion directly to the president and then begins a cat and mouse game of cloak n’ dagger, teaming with the most trusted members of the president's inner circle, including his top aide, Paul Girard (Martin Balsam), a crusty drunken Southern congressman played wonderfully by Edmond O’Brien (he won an Oscar ten years earlier for his performance in The Barefoot Contessa), and finally Jiggs cozies up to a boozy Washington socialite, Eleanor Holbrook (Ava Gardner), who knows all the town’s players and harbors secrets.

A Star is Born (1937)

A Star is Born. What a title. It promises greatness, wish fulfillment and a kind of immortality. What could sustain such a fire? What could possibly bring forth such legendary light? Even a star has humble beginnings and we meet our speck of star dust in a provincial home on a snowy day in Smalltown, USA. It is classic Americana movie making that marries depression era silents to the slow emerging prosperity of WWII America still harboring a romantic vision of manifest destiny.

There is an embittered aunt, a struggling pop, a bright but unformed kid brother, but most importantly and impressively a wise grandmother played with brilliance by May Robson. If you ever need inspiration watch her speech to Janet Gaynor's young and determined Esther, as she encourages her to follow her dreams of being an actress in Hollywood. It practically sings with the spirit of the wild west, not to mention female empowerment.

Continue ReadingLouisiana Story

If you went to film school, or took a course in college on the history of documentary film, you were probably introduced to the name Robert J. Flaherty with Nanook of the North, a 1922 silent-documentary following the lives of Eskimos that would be his first major accomplishment and is regarded as one of the first, if not the first, feature-length documentary. Though some shun the work for being scripted (which most documentaries are), it is incontestable that Flaherty followed and exposed his subjects with depth and compassion. Nanook is certainly impressive, but nothing about it placed the director on my list of filmmakers to track down; perhaps young people are often made anxious by history.

I recently stumbled upon Louisiana Story and assumed that it was a historical documentary on the place. Though it is listed, for some strange reason, as a documentary, it is really a scripted, dialogued film about a Cajun boy's adventures in a bayou. I suppose they classify it as a documentary because he and his family are just acting out their lives and adding a little extra dramatization for the camera. More intriguing than the realization that Flaherty did more than silent documentaries was the story behind how the movie came to be made.

Continue ReadingA Place In The Sun

The "American dream." Many of the WWII GIs and their wives thought they were living it. It was the goal. A place of respect in society. Materialism. Love. It was all promised…Or so they thought. The flaws in the dream were gradually exposed throughout the '50s and especially into the '60s. One of the first to do so was the great filmmaker, George Stevens, a WWII vet himself (he shot some of the most important war footage ever recorded, the liberation of Paris and the Nazi camp in Dachau). Using Theodore Dreiser's 1925 novel, An American Tragedy, as a springboard, Stevens showed the horror of the ambitious dreamer (it was also made into a rarely mentioned film by Josef von Sternberg in 1931).

What is now considered Stevens' so-called American Trilogy begins with A Place In The Sun and then goes on to include his greatest masterpiece, Shane, and then James Dean’s final film, the overlong Giant. He would follow up the cycle with the touching, but stagy, The Diary Of Anne Frank, in ’59. Unfortunately his disastrous biblical epic, The Greatest Story Ever Told, in ’65 would more or less send him into early retirement as a director (he would pop out once more, five years later, for the Warren Beatty snoozer, The Only Game In Town). A Place In The Sun, in retrospect, is the perfect peek into the dark side of America in 1951. George Eastman (Montgomery Clift), a modest, steady young man, accepts a job from his rich uncle at a factory. He gets involved with a mousy co-worker, Alice (Shelley Winters), eventually knocking her up, a major inconvenience when he meets and falls for the boss’s wealthy, fast lane daughter Angela (Elizabeth Taylor at her most stunning). The two have an intense chemistry for each other. George gets a taste of the lifestyles of the rich and famous, but he is stuck with his whiny pregnant girlfriend who is basically blackmailing him into marriage. George will do whatever it takes to get rid of Alice so he can get his share of what he thinks the world owes him.

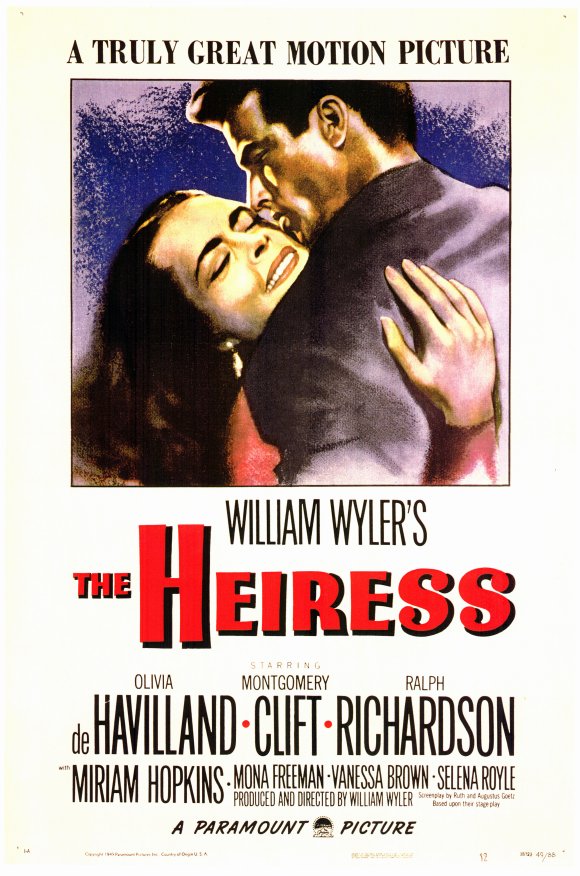

Continue ReadingThe Heiress

In some ways Olivia de Havilland may be one of the more underrated actresses of her generation. She wasn’t as iconic as some of her peers like Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis and not quite as beautiful as her rival sister, actress Joan Fontaine (Suspicion); instead of sexiness de Havilland brought a righteous intelligence to her roles. She was known throughout history mostly for playing Melanie in Gone with the Wind and for her association with the dashing actor Errol Flynn in their eight films together, most notably The Adventures of Robin Hood, They Died with Their Boots On, and Captain Blood. She had a number of other relevant roles in the ‘40s including The Snake Pit, Not as a Stranger, and Hold Back the Dawn. de Havilland won two Oscars: first, for the melodrama To Each His Own and then for her most interesting performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress, based on the Henry James novel Washington Square.

In some ways Olivia de Havilland may be one of the more underrated actresses of her generation. She wasn’t as iconic as some of her peers like Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis and not quite as beautiful as her rival sister, actress Joan Fontaine (Suspicion); instead of sexiness de Havilland brought a righteous intelligence to her roles. She was known throughout history mostly for playing Melanie in Gone with the Wind and for her association with the dashing actor Errol Flynn in their eight films together, most notably The Adventures of Robin Hood, They Died with Their Boots On, and Captain Blood. She had a number of other relevant roles in the ‘40s including The Snake Pit, Not as a Stranger, and Hold Back the Dawn. de Havilland won two Oscars: first, for the melodrama To Each His Own and then for her most interesting performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress, based on the Henry James novel Washington Square.

The late 1800s in New York City: mousy spinster Catherine Sloper (de Havilland) lives with her wise and widowed doctor father, Austin (Ralph Richardson who in real life was only 14-years-older than de Havilland), and her doting aunt, Lavinia (Miriam Hopkins). Catherine’s utterly plain and shy and unexceptional in every manner, which makes it more surprising when the handsome Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) shows up in town from California and immediately takes an interest in Catherine, wooing her with all his pretty-boy charms. Romanced for the first time, Catherine comes alive, becoming a giddy school girl utterly smitten with her suitor. The two lovebirds become engaged and plan to elope, but Austin doesn’t trust the rogue, knowing a playboy gold digger when he sees one; he tells Catherine he will disinherit her if she marries him. He also hurts his daughter when he coldly explains that Morris could have any young hottie in NY and why would he chose her if it’s not for the money? Proving Dad right, with the money not coming Morris doesn’t show up for the elopement and rushes back to California. Brokenhearted, Catherine realizes for the first time she really is a dullard who can only find love if she’s loaded with cash. And then to make matters worse, Austin dies and Catherine goes from a happy simpleton to a cold heiress. Years later Morris returns to try and get in on the money again, but the new self-empowered Catherine only pretends to buy into his oily trap and turns the tables on him instead, accepting a lifetime of loneliness to keep her dignity.

The Grapes Of Wrath

When Tom Joad (Henry Fonda) returns to his Oklahoma farm after four years in prison, he learns that nothing is what it was. It’s the 1930s, the depression is on, and his family has lost their farm and home to the bank. So begins an amazing journey for Tom - as he sees the social injustice around him he grows from petty criminal to labor activist. The Grapes of Wrath is a monumental film by a monumental director, John Ford, based on a brilliant book by another monumental figure, John Steinbeck. The truths laid out in the book and film may be just as true today as they were then. Tom leads his family from the dustbowl in search of work and a promise for a better life in California, but all they find are lies, police corruption, and corporate exploitation of desperate workers. It sounds a lot like the plight migrant workers from Mexico and Central America still face in search of the supposed American Dream.

The Grapes Of Wrath almost plays like a post-apocalyptic adventure as Tom, along with his Ma (Jane Darwell), Pa (Russell Simpson), and the preacher, Casey (John Carradine), pack the entire Joad clan into the truck and head west, where the world they encounter is a hostile and burnt out place. They are encouraged by pamphlets to head to California, but they get there to find themselves hoarded like cattle in a police state where their every move is monitored (another piece of futureshock, the dystopian state). Tom, at first naive, then confused, slowly realizes that all the cards are fixed against him and all the little people of the country. By the end, on the run from the cops, he tells his Ma in one of the great speeches in film history, "Wherever there's a fight, so hungry people can eat, I'll be there. Wherever there's a cop beatin' up a guy, I'll be there..." It’s a dark conclusion for the Joad family (and for the American Socialist dream, as WWII and then the Cold War are just around history’s corner).

Continue Reading