Herr Arnes pengar (Sir Arne’s treasure)

Subtitled “a winter ballad in 5 acts,” Herr Arne’s adventure is a bleak and beautiful masterpiece of Swedish Cinema. In the 16th century, a gang of conspiring Scotsmen are banished from the country except for their leaders, who’re locked up in a tower. They promptly escape, disguise themselves as journeymen tanners and go on a murderous rampage, looting the titular treasure from the kindly Herr Arne’s vicarage.

When they try to beat the retreat, the bellicose rogues find themselves iced in and forced to wait out the harsh winter. In the process of checking the ice, one of the evildoers (Sir Archie) falls for the sole survivor of their rampage, the young, adopted daughter of the vicar, Ellasil. She falls for him too and, before long, they figure out where their lives have intersected before. Haunted by ghostly visions, Sir Archie even recalls stabbing his beloved’s sister in the heart. And yet, their new love proves unassailable – though they’re understandably wracked with guilt and sullenly accepting of their inevitable ends.

Continue ReadingTagebuch einer verlorenen (Diary of a lost girl)

Had Tagebuch einer verlorenen come out before Die Büchse der Pandora, it would possibly be regarded as the superior film. The reasons filmschoolies seem to champion the earlier film are usually contextual. It had the first onscreen depiction of lesbians, it was the first collaboration between Pabst and Louise Brooks and it is, unquestionably, an amazing film. If you need further proof, the always safe and predictable Criterion released the first and Kino the latter. Viewed side-by-side, there’s little between the two films and the relatively lower stature of Tagebuch einder verlorenen seems to stem more from underexposure than under-appreciation.

With this film, Pabst presents one of the earliest (possibly the first) example of the Women in Prison film. Although technically not set in prison, the reform school setting is a common variation of the subgenre and allows for the same sorts of exploitation – sadism, lesbianism and repression of an innocent forced to endure cruel conditions. Pabst is, somewhat ironically, often praised for his sympathetic portrayals of the plights of women, but here (as with his earlier work) he seems to revel in the lurid situations he creates. Beginning with Die freudlose Gasse (1925) and continuing with Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney (1927) and Büchse der Pandora (1929); Pabst’s heroines are variously unloved, duped, raped, forced into prostitution and murdered. The relentless brutality, at frequent instances, approaches camp in that Teutonic manner where comedy and horror comfortably co-exist.

Continue ReadingPuppets & Demons

Several works from filmmaker Patrick McGuinn (Sun Kissed, Eulogy for a Vampire) are collected in this delightful DVD. Below are descriptions of the shorts featured, many of them done with 16mm film and Claymation, and later with digital video once the technology became available.

Stella!, 1995—Stella and her puppet boyfriend Vincent are an odd pair, obviously, who both desire Twinkies above all else and play control games with each other using the greasy sponge cake. Evolution, 1982—An impressive and colorful Claymation short about the survival of the fittest and evolution, where reptilian one-eyed monsters and dinosaurs attempt to overtake the land and devour its inhabitants while also destroying its order. Carousel of Death-Satan’s Game, 1985—Hippie culture meets really bad ‘80s fashion and Hip-Hop as Satan plays tricks on unsuspecting victims. This short has some excellent and appropriately trippy washouts that look like faded Polaroids, as well as trashy animation and some brave experimenting that made it one of my favorites in the collection. It also unfolds like a bizarre music video since there is no dialogue and reminds me of some early Spike Jonze videos. Terrence Baum: Intergalactic Assassin, 1986—This short opens with a lot of experimental shots, including layered animation of the cosmic world. It’s shot in black and white with a very paranoid vibe and classic goofiness. The film has the look of a noir and yet the out-of-sync and rushed action of a German expressionist silent film, except there is dialogue. Terrence Baum, a government secret agent, goes on a search and destroy mission for aliens from the planet Saliva. He speaks in what could only be Arnold Schwarzenegger’s voice (clips taken from other films, I assume) as he uses his only weapon, the Glutonious Maximizer, to sniff out the aliens who have come to earth disguised as bachelors in order to collect single women, who I guess are their only prey. Agnes Keedan’s Secret Plan, 1988—A crotchety and eccentric old woman goes berserk when two neighborhood children, one of whom is her domestic helper, disturb her magic wig, which comes to life and traps the children. She is then exposed as a witch and develops a potion that can transform her only friends (a jar of insects) into enough bugs to fill an entire house. Gran’ma!, 1995—A young man visits his grandmother, exposing yet another group of individuals, including the puppet Vincent, who exercise their right to love Twinkies. Only this one comes in the form of a hilarious sing-a-long with the words on the screen and everything. When the Owling Has Come, 1989—This is a satanic short where a scholar and his apprentice discuss philosophical babble and the scholar confesses that an evil muse is the source of his, and thus his apprentice’s, ethics. Shot in color with some excellent effects and lighting, this is one of the shorts with the most craft and more classic storytelling techniques. SPF 2000, 1997—Two men, Poochie and A.J., attempt to make sexual advances toward a teenage boy while he is on a picnic with his mother. This has the most absurd concept and is therefore a gem among the lot, equipped with sleazy ‘70s music and great close-ups. Oh, and an alien who crashes their party. So Many People!, 1995—A short musical about ....you guessed it, Twinkies, and how so many people love them. Ironically suggestive toward the absurdity of processed foods, this is an enjoyably tart short that is very much like a stylized TV commercial. Say Thankyou, Please,1990—A man, exhausted with the daily grind, gets home from work and receives a call from his friend telling him that he has sent a blind date to his house for dinner, against his will. So…a musical unfolds, using his friend Vincent (the puppet), about how to make pasta, which was he intends to serve.

Continue ReadingCinema 16: European Short Films, Vol. 1

16 shorts, 16 stories, 16 tales that prove shorts can have as much power as feature films. What makes these shorts stand out from others is the attention to detail, since shorts tend to be more focused. The styles vary as each work holds its own, and while it is interesting to see famed directors' shorts (often their first or beginning works), the ones that are from lesser-known directors are most refreshing. Yet– watching the works of directors such as Christopher Nolan or Lars Von Trier gives viewers more insight into what their visions were in a more attentive short form.

I was most inspired by "Before Dawn", by Hungarian director Balint Kenyeres. Simply told through its stunning visuals, the story is about refugees hiding in a high wheat field. The premise itself is challenging, and the way it unfolds is powerful and compelling. The cinematography is haunting, as the title may reveal.

Continue ReadingThe Films of Kenneth Anger, Vol. I

Wordless imagery, saturated colors, avant-garde, myth-ridden – a few of a handful of terms to describe Kenneth Anger’s short films. His work is dazzling, surreal, and certainly a hallmark that pioneered the very language of music videos.

Prior to this UCLA Film Archive high definition digital transfer, these early films of Anger were difficult to view. This collection of work is only a part of his work; several others can be found in Volume II. Here, we have his early works, Fireworks, Puce Moment, Rabbit’s Moon, Eaux d’Artifice, and Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, each savory in magical moments, imagination, rituals, and pop-song splendor.

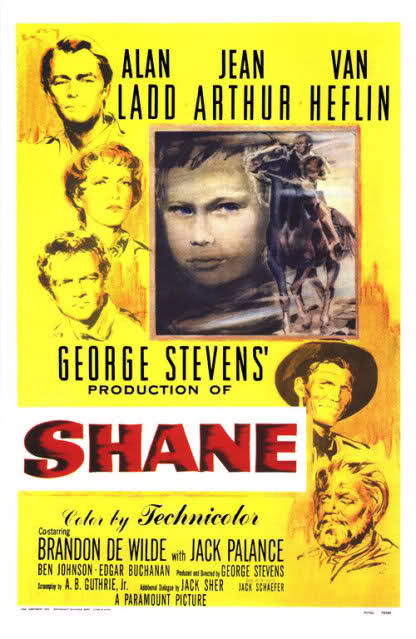

Continue ReadingShane

John Ford may have brought the Western out of the B-movie jungle and into the respected leagues (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, The Searchers, etc.), but George Stevens took the workman’s template and made it beautiful. With his masterpiece, Shane—maybe the greatest American Western of all time—he infused the genre with even more mythology than it already relied on. Shane is the film that influenced the Western Revisionists and Postmodernists more than any other; Sergio Leone and his Italian friends in the Spaghetti Western scene were all obsessed with Shane and it shows in their work. If the plot of Shane sounds familiar that’s because it’s been recycled dozens of times in everything from Westerns (Pale Rider) to post-apocalyptic junk (Steel Dawn). Shane may have more to say about the Hollywood myth and romanticism of violence, and more poetically, than any film before or since.

John Ford may have brought the Western out of the B-movie jungle and into the respected leagues (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, The Searchers, etc.), but George Stevens took the workman’s template and made it beautiful. With his masterpiece, Shane—maybe the greatest American Western of all time—he infused the genre with even more mythology than it already relied on. Shane is the film that influenced the Western Revisionists and Postmodernists more than any other; Sergio Leone and his Italian friends in the Spaghetti Western scene were all obsessed with Shane and it shows in their work. If the plot of Shane sounds familiar that’s because it’s been recycled dozens of times in everything from Westerns (Pale Rider) to post-apocalyptic junk (Steel Dawn). Shane may have more to say about the Hollywood myth and romanticism of violence, and more poetically, than any film before or since.

Based on the novel Shane by Jack Schaefer, the film is seen through the eyes of a young farm boy, Joey Starrett (Brandon De Wilde), in the settled territory of Wyoming. Life’s a struggle for his proud but modest parents, Joe (Van Heflin) and Marian (Jean Arthur). Besides the usual struggles against nature in the tough terrain, the area is owned by the ruthless baron, Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer), who is trying to force the Starretts and the other local homesteaders off their land. When a drifter named Shane (Alan Ladd) shows up on horseback, the Starretts take him on as a ranch hand and he gets involved in the conflict between the wholesomely innocent homesteaders and the greedy Ryker and his posse of hired goons.

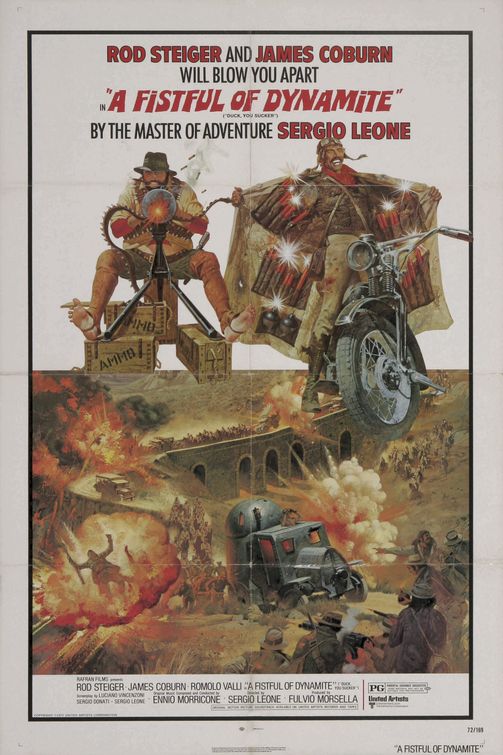

Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite)

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

Throughout Leone’s Eastwood “Man with No Name” trilogy, each film was made back-to-back-to-back (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) and each got more progressively ambitious in both scope and ambition as their popularity grew. Finally, the director peaked with his follow-up, Once Upon a Time in the West, an accumulation of all the ideas he had been building towards and both the ultimate post-modern western and one of the true film masterpieces of the 1960s. He finally took a break (three years) before returning to the screen with the eccentric Duck, You Sucker (afterwards he would take an even longer break, not being a credited director for 11 years). In some territories the film was titled Once Upon a time in the Revolution or A Fistful of Dynamite but it would not fully fit with his first four flicks (we all tend to ignore his unrecognizable debut The Colossus Of Rhodes in ’61). Everything about this new film felt slightly tweaked. Its tones moved from comic to dramatic to sentimental to tragic to cartoony much less gracefully than in his past work. The setting moved south to Mexico and the period moved up a couple decades. Where Once Upon a Time in the West had a deliberate pace, the strands perfectly came together and justified their speed, while at almost 160 minutes Duck, You Sucker sometimes just feels long and, worse, indulgent. But luckily that indulgence and the hint of a director slightly lost in his creation proves to be both fascinating and entertaining. And just as westerns had been reinvented in the ‘60s, the ‘70s saw another seismic shift where movies as diverse as Duck, You Sucker, El Topo, The Missouri Breaks, and, finally, Heaven’s Gate would help to kill the genre for a generation.

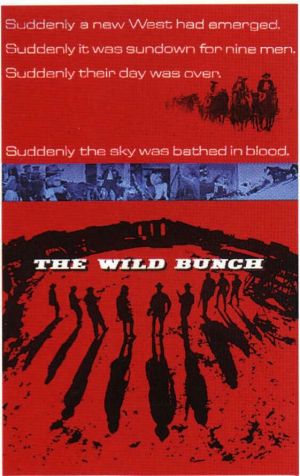

The Wild Bunch

As the western genre in America became more and more watered down by television, Sam Peckinpah singlehandedly turned the western on its head; his The Wild Bunch shocked 1969 audiences with its almost apocalyptic, misogynistic, and violent vision of a dying era. By today’s standards The Wild Bunch is still a nihilistic masterpiece. The action and graphic carnage on screen are still staggering and utterly exciting. And along with Battleship Potemkin, Psycho, and Bonnie and Clyde, it’s still one of the gold standards for incredible cutting-edge editing of violence and death. The film is bookended by two of the best pieces of choreographed mayhem ever put to screen where the Bunch engage in shootouts so violent and intense that the film got an X rating then and even got an NC-17 rating when it was re-released in the ‘90s (both ratings were negotiated down by the studios). The editing and mix of film speeds, including slow motion, have been ripped off and become a standard in operatic action scenes since—just check out all of John Woo’s best (Hong Kong) films; they’re direct grandchildren of The Wild Bunch.

As the western genre in America became more and more watered down by television, Sam Peckinpah singlehandedly turned the western on its head; his The Wild Bunch shocked 1969 audiences with its almost apocalyptic, misogynistic, and violent vision of a dying era. By today’s standards The Wild Bunch is still a nihilistic masterpiece. The action and graphic carnage on screen are still staggering and utterly exciting. And along with Battleship Potemkin, Psycho, and Bonnie and Clyde, it’s still one of the gold standards for incredible cutting-edge editing of violence and death. The film is bookended by two of the best pieces of choreographed mayhem ever put to screen where the Bunch engage in shootouts so violent and intense that the film got an X rating then and even got an NC-17 rating when it was re-released in the ‘90s (both ratings were negotiated down by the studios). The editing and mix of film speeds, including slow motion, have been ripped off and become a standard in operatic action scenes since—just check out all of John Woo’s best (Hong Kong) films; they’re direct grandchildren of The Wild Bunch.

The legend of director Sam Peckinpah has taken on mythical proportions; he was a man out of time, a hard drinkin’ visionary with a death wish. One fact is definitely true: he was an ex-TV western director trying to find a place in features. His Ride the High Country was considered a little gem while the financial disaster and critical drubbing of Major Dundee almost ended his film career (a half-century later, it’s now deservingly considered an outstanding film). With Waylon Green (director of crazy killer insect cult flick The Hellstrom Chronicle), Peckinpah wrote the perfect vehicle to truly strut his romantically ugly version of the end of the Old West.

3:10 To Yuma

The Western is showing signs of regained life, and no picture is a better example of the renascent genre than 3:10 to Yuma. Inspired by an Elmore Leonard story and originally filmed in 1957 with Glenn Ford and Van Heflin, the remake sports compelling performances by its leads, Russell Crowe and Christian Bale.

The notorious murderer and robber Ben Wade (Crowe) is captured, and struggling farmer Dan Evans (Bale) accepts an offer of $200 to join a motley posse and pack the criminal onto a train to the state prison at Yuma. During an arduous, violent journey, the group is menaced by renegade Indians, rogue lawmen, and Wade’s gang, and the charismatic, deadly Wade presents a threat all by himself.

Continue ReadingHigh Plains Drifter

Oh, the seventies, the best decade for movies ever! So often I see a film from that period and think, "they would never allow that to happen in a movie today." Case in point: High Plains Drifter. The year, 1973. This was a big movie for Universal, a big budget film. It was directed by and starred Clint Eastwood, who at that time was the biggest megastar in the world. Clint was playing the "hero" of the picture. Now you won't see this from a megastar in a movie today: in the first ten minutes or so he goes and rapes a woman, brutally in the light of day, while the people of the town ignore her plea for help (in Clint's defense, later in the film she comes back for more).

That's not the only naughty shenanigan Clint gets into. Clint's stranger, the new man in an unusually picturesque seaside Western town, is hired by the town's business class to protect their property from some revenge-seeking tough guys who recently got out of jail (those same business owners once employed them and when they got out of control, framed them and sent them to jail). And now Clint is the town's new protector and he seems to be hell-bent on his own kind of revenge against the town, in the form of humiliation. He takes advantage of his open tab to spend, he appoints the town little person as town sheriff and then, in preparation for the returning outlaws, he makes the town paint itself red (even the church is forced into being covered in paint).

Continue Reading